by Russ Mullen

Everyone needs a special place,

Where mind can wash and clean.

A place where heart can heal itself,

And dreams are clearly seen.

– That Special Place – R. Mullen

I grew up on a diversified farm in southwest Iowa during the 1950s and ‘60s when chickens, hogs, cattle, hay crops and pasture dotted farm landscapes. Farmers used small tractors by today’s standards, bulldozers on the farm were rare, and grain crops genetically modified for use of specific herbicides had not been invented. Almost every farm had timber, brushy waterways and weedy fencerows. Even farms in central Iowa with flatter land had more timber, brush and grassy fencerows than today. Our family trapped, hunted, fished and farmed so it was easy for me to observe places in nature that provided sanctuaries for wildlife:

~ The young doe that jumped up out of the weeds while I walked along a brushy waterway  looking for a missing cultivator shovel, her two spotted fawns stumbling to keep up with her as she led them to the entryway of a thick forest of oak and hickories.

looking for a missing cultivator shovel, her two spotted fawns stumbling to keep up with her as she led them to the entryway of a thick forest of oak and hickories.

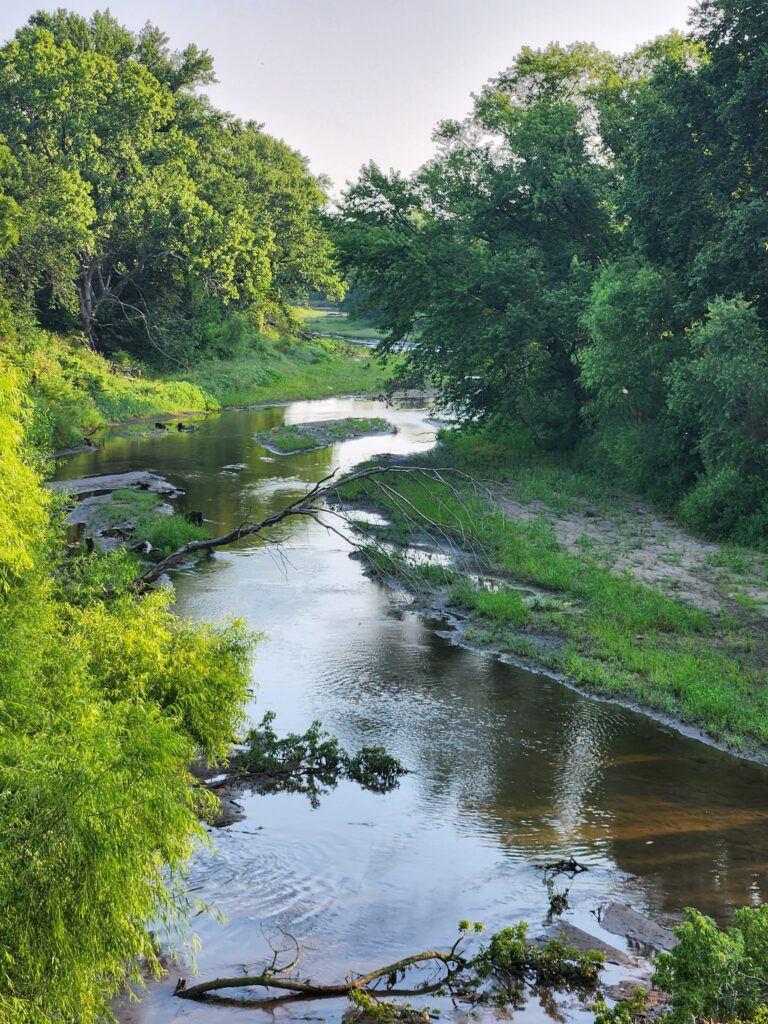

~ Fingerling perch furiously swimming to a tree-shaded pool of still water bordering a trickling stream, as my shadow interrupted their womb of watery quiet.

~ The dipping and bobbing head of a colorful, ring-necked, male pheasant rushing nervously toward a corner stand of six-foot tall prairie grasses as I checked cows in our pasture.

~ The burst of brown-, black- and gray-camouflaged sparrows disappearing into the nearby  black hole of a sun-shaded forest as I saw a hawk’s silhouette floating into their feeding area.

black hole of a sun-shaded forest as I saw a hawk’s silhouette floating into their feeding area.

~ Even Dad had a natural sanctuary. A week before his land payment deadline, I saw him grab his old, crooked cane fishing rod, the cream-colored sisal string wrapped in spirals around the pole with a red-and-white bobber hanging on for dear life. His right hand held a metal “Butternut” coffee can, half full of feedlot-fed worms. He disappeared over the hill toward his favorite fishing hole – a naturally air-conditioned spot under the overhang of a 75-year-old cottonwood tree near quiet moving water, a stream that no longer held fish.

The point is that all species need sanctuaries to flourish – physical spaces in nature that provide safety, acceptance and freedom. And in a farming state like Iowa, we have lost these sanctuaries at an alarming rate. Ninety-five percent of Iowa’s wetlands have disappeared, more than half of the forests, and many wildlife species are in decline due to agriculture intensification. But it’s not an impossible situation. We can embrace, value and implement farmland sanctuaries.

One of my early boyhood memories of a previously, unexplored sanctuary occurred only a short distance from our farmstead, on a dirt road in southwest Iowa. It was a silent, undisturbed wetland, a 20-acre space of “economically worthless land.” It drew me there because I wanted to apply my newly-learned trapping skills after watching my father manage his trapline. I was determined to become the “Daniel Boone” of the modern era.

I walked out of the driveway just before dawn, traps slung over my shoulder, and headed south to the wetland. It was one of those crisp fall mornings and every sound was distinct. Bird calls echoed off the road toward me as I topped the last hill. Conversational notes of mergansers, wood ducks, mallards and geese – talking and laughing – ricocheted into my ears.

I crossed the rusted fence bordering the wetland and entered a foreign land. Mounds of soil, claimed by patches of reeds and cordgrass, stood above pools of water like unbridled acne on nature’s pockmarked skin. Hopscotching on mounds of soil, my foot slipped, throwing me forward. My gloved hands dove into the muck below and sank deeper and deeper until my face entered the murky water. The water tasted stale and had the aroma of sweat-stained socks that should have been washed three days earlier. My hands, covered in a dark, creamy sludge, smelled revolting at first, until I remembered Dad’s description of nature’s perfume. I regained my footing and stood, transformed into a swampland rat – a soddened, furless animal standing in a strange world only one-half mile from where I lived.

I crossed the rusted fence bordering the wetland and entered a foreign land. Mounds of soil, claimed by patches of reeds and cordgrass, stood above pools of water like unbridled acne on nature’s pockmarked skin. Hopscotching on mounds of soil, my foot slipped, throwing me forward. My gloved hands dove into the muck below and sank deeper and deeper until my face entered the murky water. The water tasted stale and had the aroma of sweat-stained socks that should have been washed three days earlier. My hands, covered in a dark, creamy sludge, smelled revolting at first, until I remembered Dad’s description of nature’s perfume. I regained my footing and stood, transformed into a swampland rat – a soddened, furless animal standing in a strange world only one-half mile from where I lived.

Slowly and quietly, I moved through the marsh looking for good places to set traps. Waterfowl, although wary, accepted me and didn’t fly. A muskrat, perched on a mound 25 yards away, stared at me and leisurely entered the pool of water, disappearing beneath the surface, ripples showing me his direction. I began focusing, not only on what was in front of me, but on the landscape around me. The area was alive with movement.  The surface was dancing, undulating in synchrony with animal sounds. A white wing flashed ahead, another to my left. Two wings lifted and vanished. Water rippled and vibrations glistened in silver, something swimming below in the shadows of reeds. Iridescent shards of green flashed from mallards swimming in and out of the yellow shafts of sunrise that pierced the marsh. Ducks, adorned with red, purple and orange feathers, silently glided and circled in do-si-do fashion among the vegetation. Cattails, reeds and sedges nodded and swayed in the morning breeze – hiding shy tenants inside.

The surface was dancing, undulating in synchrony with animal sounds. A white wing flashed ahead, another to my left. Two wings lifted and vanished. Water rippled and vibrations glistened in silver, something swimming below in the shadows of reeds. Iridescent shards of green flashed from mallards swimming in and out of the yellow shafts of sunrise that pierced the marsh. Ducks, adorned with red, purple and orange feathers, silently glided and circled in do-si-do fashion among the vegetation. Cattails, reeds and sedges nodded and swayed in the morning breeze – hiding shy tenants inside.

Small, playful birds sang different notes and played tag among the taller reeds. Geese and ducks conversed in deeper tones about serious topics while watching and scolding their offspring. I smelled the faint pungent odor of muskrats and mink, and spotted their runs and dens. This place was a kingdom, with districts and cities of happy, contented creatures – some that you could see, some that you couldn’t.

Funny, on the way home, I looked back from the hill overlooking the marshland. I couldn’t see movement, I couldn’t feel it, I couldn’t hear it and I couldn’t smell it. The place looked  quiet, serene and abandoned – like a dream that I had imagined.

quiet, serene and abandoned – like a dream that I had imagined.

I never caught much out of that swampland that fall. Setting traps in that quagmire was pure hell for a two-legged animal like me. It made me appreciate dry land, something I can walk on, drive tractors on and raise crops on. But trapping made me enter the bowels of a marshland. I could feel its insides, smell its stink and taste its dank and sour water. What was inhospitable to me, was heaven to other animals and plants. I witnessed the beauty of wetlands learned by feel, touch and smell, and by witnessing the passionate devotion of animals and plants who thrived there. It was also my source of pain and sorrow when the land was bought and tiled 40 years ago.

I drive by that wetland location every time I go to my farm now. The road is still a dirt road, but all the birds and wetland animals and plants are gone. The marshland is silent, vanquished by the tilling of the soil and the removing of standing water.  It is now only a memory within a large, flat 40-acre field – a field of corn one year and soybeans the next.

It is now only a memory within a large, flat 40-acre field – a field of corn one year and soybeans the next.

Dad is still with me when I drive by. I recall his laments, several months before he died, of how the land has changed since he was a young man in the 1930s and 40s. His lamentations gave voice to the landscape, but I didn’t realize it until decades later. At the time, I categorized it as old-man speak. But after seeing 100-year changes in the landscape through Dad’s eyes and in my lifetime, I now understand. Long-term changes in landscape can be seen only through time. They occur silently and relentlessly, and the new landscape becomes the norm for younger people. It’s a progression with no end.

I don’t roll down my window anymore, like Dad did, to hear the raucous, festive sounds of the wetland. The only sounds today are the soft, rustling crop leaves on a windy day, silent currents carrying away nature’s memories. But I am glad that I walked inside that marshland and felt and heard its heartbeat years ago. A young farm boy, fancying a coonskin cap with a long furry tail, experienced that place. That little wetland, a sanctuary for many species, was destroyed within a week by human decision. But it imprinted a memory on countless generations of mink, muskrat, duck, geese, frogs and many other species, including my family. That memory will last until we die.

The great thing about farmland sanctuaries is that they are physical – they can be built, rebuilt or preserved. No sanctuary is too small. Nature will supply the products and the labor. We need only to value sanctuaries economically, not just ethically. Economic incentives, artificially-supported markets and policy regulations have favored and rewarded the tremendous loss of physical sanctuaries in our farm landscapes in the past. But today, we could use those tools to establish value and to reward landowners for providing sanctuaries on their land. Modest, innovative changes in our county, state and national tax laws would help. Using small percentages of already existing taxpayer-supported subsidies, like ethanol-blended gas that supports corn production, could easily create sanctuary value right now. Fostering mini-sanctuaries on private farmlands could lead to large-scale positive impacts on our natural plant and animal diversity in the nation’s agricultural heartland.

The time is right. The next 50 years will see landscape manipulations and loss of biodiversity at a much greater scale than those in my lifetime or my father’s. How satisfying it would be… to own a farmland sanctuary, or to invest in or support a farmland sanctuary program. How rewarding… to preserve or create special places where a myriad of species feel safe, accepted and valued.

Copyright © 2023 by Russ Mullen

Photographs courtesy of Rich Mullen and Jill Mortensen.

Russ Mullen

Russ Mullen is Professor Emeritus of Agronomy, Iowa State University. He was a scientist and educator during his 41-year university career.

He is a lover of agriculture, outdoors, nature’s art and biodiversity.

Read more of Russ Mullen’s writings in earlier episodes of Blazing Star Journal: The Great Mullen Cattle Drive, part 1 and The Great Mullen Cattle Drive, part 2.