The old red pickup truck rolled  through Mason City and Clear Lake, past Garner and Britt. I drove as Teri Jean studied the map, flicking cigarette ashes out of the window, blond hair flying in the breeze. It was 1978, long before cell phones or GPS. In the truck bed, under the metal topper, rode Schulz and his gang of near life-size hand-and-rod puppets with papier mâché heads and protruding, soulful, movable eyes. Schulz was the head puppet. He called the shots. He wore a purple shirt, tan pants and brown boots and sported a red beard with a bald pate. He’d started life as a king, but he soon shed his crown and became a sort of “every-puppet”, doling out sage advice to the other puppets and even to us, his human manipulators. He and his pals shared the space with the stage, four plywood panels, each designed to look like a house, with a pitched roof silhouette and a window cut-out.

through Mason City and Clear Lake, past Garner and Britt. I drove as Teri Jean studied the map, flicking cigarette ashes out of the window, blond hair flying in the breeze. It was 1978, long before cell phones or GPS. In the truck bed, under the metal topper, rode Schulz and his gang of near life-size hand-and-rod puppets with papier mâché heads and protruding, soulful, movable eyes. Schulz was the head puppet. He called the shots. He wore a purple shirt, tan pants and brown boots and sported a red beard with a bald pate. He’d started life as a king, but he soon shed his crown and became a sort of “every-puppet”, doling out sage advice to the other puppets and even to us, his human manipulators. He and his pals shared the space with the stage, four plywood panels, each designed to look like a house, with a pitched roof silhouette and a window cut-out.

“Turn left!” The truck screeched around the corner and headed into Corwith, the site of our first ever school residency. A couple of weeks earlier Teri Jean and I had been sitting at the round table in the kitchen, nursing our coffee, when we got a call from the Iowa Arts Council. Would we like to try doing some five-day school residencies through the newly minted Artists in the Schools program? Of course we would! And here we were, driving past the bank, the café, the hardware store and pulling into the elementary school parking lot. Our tiny 2nd grade teacher-sponsor was there to meet us and help us unload our pick-up truck. She picked up a wooden panel and started across the parking lot to be accosted by a strong wind, looking as if she was about to take to the sky like Mary Poppins.

We all conquered the wind and set up in the gym under the basketball hoop. The kids filed in grade by grade, the kindergartners following their teacher like baby ducks and sitting “criss cross applesauce” on the floor in the front row. The 6th graders sat in the back. Schulz’s big moment was about to start:

Schulz here: Whoa, look at all those kids! Boy, I hope they like me! But why wouldn’t they? Don’t worry, Schulz, just act out the story, Monkeys and Owls! I get to play a baker, and I have to bake a 30-layer cake with a miniature castle and a waterfall on top, made out of frosting. But I feel awful because I just ate six—count ‘em—six chickens, and I need a nap! Well, the story goes on and I get Till Eulenspiegel to do the work for me. Only, instead of baking the cake, he bakes monkeys and owls! Don’t ask me how he got that mixed up, but it was hilarious, and the kids thought so, too. WHEW!

Schulz here: Whoa, look at all those kids! Boy, I hope they like me! But why wouldn’t they? Don’t worry, Schulz, just act out the story, Monkeys and Owls! I get to play a baker, and I have to bake a 30-layer cake with a miniature castle and a waterfall on top, made out of frosting. But I feel awful because I just ate six—count ‘em—six chickens, and I need a nap! Well, the story goes on and I get Till Eulenspiegel to do the work for me. Only, instead of baking the cake, he bakes monkeys and owls! Don’t ask me how he got that mixed up, but it was hilarious, and the kids thought so, too. WHEW!

After the show, we headed into the classrooms, one by one, and started making puppets with the kids. We began to develop ideas, schedules, and teaching techniques that would stand us in good stead for the next twenty years. After that first trip to northern Iowa, the word got out, and soon we were doing an average of two five-day residencies a month, sometimes more, in all of Iowa’s ninety-nine counties. We stayed with families, which meant we were “on” all day and all evening. Our host family one week had kids who were super excited to have the guest puppeteers staying with them. It was getting to be a little much.

“Hey, how about this?” I said to Teri Jean. “We tell them we need to get into school in the evening so we can work on a new show.”

“But we’re not working on a new show, are we?”

“So??”

“Oh! I’ll bring my Jane Fonda tape!”

Teri Jean figured out how the VCR in the school library worked and, before we knew it, we were doing aerobics with Jane and her crew.

“Hi, Jane!”

“Hi, Betty!”

“Hi, Frank!”

“Hi, Teri Jean!”

“Hi, Monica!”

And away we went! One-two-three-four-again! One-two-three-four-again! And again, in the next town. And the next town. Sometimes we actually worked on a new show, but only after we’d worked out with Jane!

A residency in the mid-80s took us to Cascade, a little town near our hometown, Dubuque. I stayed with my mom, Teri Jean stayed with her sister, and we commuted to Cascade to work with Mrs. Smits, a gold star first grade teacher. She had 31 students, mostly “slow learners”. We started by passing out sheets of newspaper and taping strips of masking tape to their desks.

“The newspaper is your puppet’s brains. Look at the brains and see what your puppet is thinking about today. Now crumple the brains, fitting them over your finger. Your finger is the brain stem.”

“The newspaper is your puppet’s brains. Look at the brains and see what your puppet is thinking about today. Now crumple the brains, fitting them over your finger. Your finger is the brain stem.”

Furious crumpling ensued.

“Take your longest strip of tape and wrap it around the brains. Wrap the other pieces over the top and under the bottom and you have your puppet’s skull!”

Next, we passed out the clay-like papier mâché and watched as 31 heads bowed over desks and worked intently forming the features of their chosen characters, then carefully brought them to the front of the room and lined them up to dry. The next day, after the puppet heads had dried, we passed out paints and watched the explosion of six-year-old joy. Our main problem was making sure they stopped painting!

Next came bodies and hair. This was a little more tedious and involved standing in line at the hot glue gun, which had to be operated by an adult. To make the waiting easier, Teri Jean assigned the kids to bring a joke, and we regaled each other with silly jokes while the puppets got their outfits and hairdos. Why was 6 afraid of 7? Because 7 8 9! What did the nose say to the finger? Quit picking on me! What do elves learn in school? The elf-abet! Gales of laughter!

Sonny was a sweet little boy with a big smile and no self-control. He loved the hand puppet he made, especially when he realized its hands, his fingers, could be used as pinchers, and little girls all over the room squealed as Sonny’s puppet pinched them. Mrs. Smits brought order with a withering glare. She had eyes like a fly: in the back of her head and on all sides.

After the puppets were done, we taught them some movements: walking, running, going up and down imaginary stairs, sleeping, sneezing, what have you. We were getting them ready to perform for the second graders, whom Mrs. Smits had invited to watch. There was a problem. The kids had their movements down, but they simply didn’t comprehend that they had to hold their puppets up over the curtain if anyone was to see the clever movements. No amount of “hold your puppet up!” sunk in. Teri Jean had an idea. “OK, kids, I’m going to show you some more moves! Sit down in front of the curtain!” She stepped behind the curtain and held her puppet low.

“Look! Somersaults! What do you think of that?”

“We can’t see anything!”

“Why not?” You could almost hear the penny drop.

“You’re not holding your puppet up!”

Whew! Just in time! The second graders arrived, and Mrs. Smits’s first graders did just fine!

Hey, Schulz here again; my turn to talk! Remember the first time we had breakfast in a café? I think it was the café in Wesley. We thought we could just waltz in there and eat breakfast like anybody else. Ha! Every head in the place turned when we walked in. You could hear ’em thinking, what are those gals and that puppet doing in OUR cafe! Sure enough, not a single gal anywhere! A whole row of old farts all dressed in overalls, seed caps, and shitkickers. We sat down, ordered our breakfast, and little by little, the good ol’ boys started talking again. Don’t know why they were so worried about us hearing. It was mostly weather talk and the like! Too much rain, not enough rain, is it gonna freeze tonight, can I get into the fields, no good help, kids today, on and on. Boy, those eggs and hash browns were tasty, though! You could tell by the taste and the color of the yolks…those eggs came from backyard chickens!

Hey, Schulz here again; my turn to talk! Remember the first time we had breakfast in a café? I think it was the café in Wesley. We thought we could just waltz in there and eat breakfast like anybody else. Ha! Every head in the place turned when we walked in. You could hear ’em thinking, what are those gals and that puppet doing in OUR cafe! Sure enough, not a single gal anywhere! A whole row of old farts all dressed in overalls, seed caps, and shitkickers. We sat down, ordered our breakfast, and little by little, the good ol’ boys started talking again. Don’t know why they were so worried about us hearing. It was mostly weather talk and the like! Too much rain, not enough rain, is it gonna freeze tonight, can I get into the fields, no good help, kids today, on and on. Boy, those eggs and hash browns were tasty, though! You could tell by the taste and the color of the yolks…those eggs came from backyard chickens!

In the early years, we spent many weeks in a classic little river town on the Mississippi. During one of these weeks, we performed in ten schools, two each day. Our show was The World’s Greatest Fisherman, a Norwegian folktale about a placid fisherman and a trickster fox. The fox sees that the fisherman has a string of fish in his wagon. He decides to play dead, hoping the fisherman will pick him up and throw him in the wagon for his fur pelt. He does, and hilarity ensues.

Teri Jean played the part of the fox in an overhead mask and vest, which she donned in the teachers’ lounge, leaving the black tunic she usually wore over black tights and leotard hanging over a chair. The fox entered through the audience. At the end, the fox exited through the audience to the teachers’ lounge, where Teri Jean removed her fox costume, put on her tunic, and came back to the stage.

I worked the fisherman—played by Schulz— and wore my tunic over tights and leotard during the whole show. It was Friday morning, the last day, second to last show of the week. The kindergarten teacher walked in, followed by her charges who sat on the gym floor, forming the first row.

“These two shouldn’t be sitting together,” she told me with a hint of malicious glee as she seated them next to each other. The rest of the audience came in, the principal introduced us, and the fox came in through the back of the audience, startling and delighting the kids. When the fox reached the front row, the two little rascals who should have been separated let loose. One of them stood up, reached through the fox’s open mouth, and poked Teri Jean in the face. The other grabbed her legs. The teacher sat impassively by with a vindictive little smile on her face. This continued. Other kids joined in the harassment. Teri Jean tried to stay out of their way and finally resorted to “accidentally” stepping on a finger or two. It was all we could do to get through the story. As soon as it was over, Teri Jean came backstage, ripped off the fox costume, and hissed.

“Gimme your tunic!”

Obediently, I took off the tunic and handed it to her. She put it on, stalked out, and faced the audience.

“You kids should be ashamed of yourselves!” she yelled. “Harassing someone who’s just trying to put on a good show for you! Who taught you to behave like that? Your parents would be horrified! And you teachers,” she screamed, pointing straight at the offending teacher. “Shame on you! What kind of example are you setting for your kids?” Dead silence in the audience!

She marched through the audience to the teachers’ lounge, wearing my tunic and leaving me in my tights and leotard, fat rolls—real and imagined—bulging out. I couldn’t show myself like that, but I couldn’t just do nothing!

That’s when I saved the day! I poked my head through the stage window and talked to the kids. “Hey, kids, I think Teri Jean’s feelings are kind of hurt. Why don’t we apologize? OK now, all together, ‘We’re sorry, Teri Jean!’”

“That was genius, Schulz!”

It worked. 300 voices chanted, “We’re sorry, Teri Jean!” Teri Jean heard, came back, graciously accepted the apology, and returned my tunic. Whew!

Most of our residencies were in grade schools, but we did summer camps, halfway houses, facilities for the developmentally delayed, county homes, senior centers, even high schools, especially of the alternative variety.

For a few years in the 1980s, The Iowa Arts Council sponsored residencies in county homes, care facilities for disabled and less affluent people. These homes were always in the country with sizable grounds. At one time they had all had large gardens and livestock, and the residents were responsible for their care. The homes were usually large, brick, three-story houses. Each resident had a bedroom; living and dining areas were shared. Their quality varied, to say the least.

We were asked to do a residency at one of the better homes, the Cedar County Home outside of Tipton, Iowa. We agreed to seven meetings, twice a week for three and a half weeks. We made hand puppets and built a wooden puppet stage in their woodshop.

Everyone sat around the large dining room table to work on the puppet heads. They were soft-sculpted out of discarded nylon stockings. The toes were stuffed with pillow stuffing to form the shape of the head. Then features were pinched off and secured with stitches to form noses, lips, eyelids, and ears.

Everyone sat around the large dining room table to work on the puppet heads. They were soft-sculpted out of discarded nylon stockings. The toes were stuffed with pillow stuffing to form the shape of the head. Then features were pinched off and secured with stitches to form noses, lips, eyelids, and ears.

Ruby had obsessive compulsive disorder and had trouble stopping.

“Ruby,” I said. “Your puppet’s nose is long enough! Time to stop and move on to a different feature.”

Ruby couldn’t stop, and soon the nose went over the top of the head and down the back.

Eldon loved painting, but before he could paint, the stage had to be built. He took us to the woodshop and we breathed deeply, relishing the aroma of freshly sawed wood. He and another resident were building a classic hand puppet stage. When they finished, they put it out in the gravel driveway to paint, and Eldon chose a color and found a paint brush. We didn’t think it was necessary to supervise him; what could go wrong with such a simple task?

“Eldon!” said Teri Jean, checking on him. “Pick up your brush! Don’t drag it in the gravel!!”

Too late! Every brush stroke started at the top of the stage, made its way down, and ended up collecting gravel which was then deposited on the stage with the next brushstroke. When Eldon had finished, we had a stage with a unique textured surface!

Then it was time to practice working the puppets and rehearse the show. Some of the residents designed a program and invitations, which were sent to the neighbors and to a Tipton preschool.

The big day arrived, the last day of our residency. Excitement ran high as the audience assembled. I narrated as the residents worked the puppets and Teri Jean supervised the backstage, making sure everyone had what they needed to pull off a good show. The neighbors and the preschoolers sat enthralled and rewarded the performers with loud applause. I think we felt at least as good as our puppeteers did!

One summer we spent a week in western Iowa at a halfway house for teen girls. My 15-year-old niece, Deborah, came along to help and serve as a bridge to the other teens.

“Puppets! Puppets are for babies!” This was going to take some convincing! But crafts are a universal language, and once the girls got their hands dirty making puppet heads, everything came into focus.

We had a plan. We were making characters for a favorite Grimm’s fairy tale, The Fisherman and His Wife. At the end of the week, we would perform the show. You’ve heard it: a poor fisherman catches a magic fish who grants wishes. His greedy wife keeps wishing for more and more, including a castle and a cathedral, but when she wishes to rule the universe, the fish puts them back in the shack they started in. We liked the story because it was about greed and lust for power and what happens when you let those desires take control of your life. We also liked it for the practical reason that there was lots to make: since the wife changes clothes every time a wish is granted, four different girls made puppets of this character, each in a different, fancier outfit: one in rags, one in a pretty dress, one in a robe and crown, and one dressed as the Pope! We made all the different dwellings as well as a fancy, whimsical fish.

There was one problem: the story as told by the Grimm Brothers presents the wife as a nasty shrew who orders her husband around. To me that was incidental, not really what the story was about, but Deborah reported that the girls were outraged!

“You guys have been talking to them about girl power and how they can do anything, and the role model you give them is a bullying shrew!”

Hmmm. We hadn’t thought of it that way! It was an easy fix: we had the husband and wife in cahoots with each other and made it into an equal opportunity greed-and-lust-for-power tale.

That story has followed me all of my life. I recently created yet another version of it and, as I wrote the equal opportunity script, I thought about those long-ago girls who are, I suppose, middle-aged women by now. Wonder if they ever think about their puppets.

Copyright © 2022 by Monica Leo

Monica Leo

Hand, Shadow, Rod

Monica Leo is a first generation American, born to German refugees in the waning days of World War II. After the war, her parents ordered a set of Kasperle hand puppets from a German craftswomen, and Leo began telling stories with puppets. A graduate of the University of Iowa with a major in art and a minor in English, she studied for two years at the State Art Academy in Düsseldorf, Germany, with Joseph Beuys.

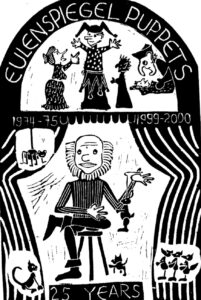

Since 1975, Leo has been creating and performing as founder and principal puppeteer of Eulenspiegel Puppet Theatre. Eulenspiegel’s home is Owl Glass Puppetry Center, a regional puppetry center in West Liberty, Iowa.

Since 2005, Leo has written the Scene Between column for The Puppetry Journal, a national quarterly magazine produced by Puppeteers of America. She has written for the Wapsipinicon Almanac and writes the plays for Eulenspiegel Puppet Theatre. Leo illustrated Marcel and the Dirtball, by Anne Leo Ellis, published by the Pterodactyl Press in 2002.