Opening the Chances for a Mess

What happens when justified frustrations are left simmering?

My mom had a large ominous-looking pressure canner. It was a giant cast aluminum pot with a small pressure gauge on the top. It held seven one-quart canning jars. It was great for canning meat and low-acid foods which couldn’t be preserved with a simple hot water bath. Using it always made her a little nervous.

“Stand back. I’m going to open the valve and let out some steam. You never know what can happen. Kathleen tried to let off steam and the gasket failed. She ended up with red beets on her kitchen ceiling.”

This repeated story was enough to send me to a distant kitchen corner. With my hands over my head and my thumbs in my ears, I’d crouch in the corner farthest from the stove. Mom turned the valve and with a loud whoosh, steam rushed out.

The risk was worth it. Steam and pressure can transform food into preserved nourishment for future sustenance.

We never ended up with beets or beans on the ceiling but pots and people under pressure can be precarious. They need to be handled with care.

In some ways, my family seemed like a pressure canner ready to explode if the wrong valve was turned.

My dad spouted off while doing chores. In the safety of the milking stable, with its line of cows waiting to be milked, he mumbled and shook his head. As he moved the milker from cow to cow, he quietly explained and re-explained the situation. He couldn’t shout. That would scare the cows. He couldn’t confront the person he was upset with, that wouldn’t fit with the Mennonite ideal of kindness. When you were ready to explode, you needed to find ways to carefully spout off. The cows knew Dad’s side of the argument. They heard about the pressures he felt – the pressure to fix the relationship between his sister and his wife, the pressure to move to a different farm, a farm that wasn’t linked to his family, and the pressure to keep up a good appearance. The cows calmly chewed their ground corn and listened. Next week the cows listened again. The spouting contained variations on the same topics, or so I imagined. Mingled with the smell of cow manure, I caught enough words to know that life can be tricky, and explosions may be just around the corner.

The cows never seemed to answer the persistent question, “How do you handle an older sister who tries to run your affairs, and find a way to remain kind?”

The cows never seemed to answer the persistent question, “How do you handle an older sister who tries to run your affairs, and find a way to remain kind?”

My mom found her own way to spout off. She took a comfortable chair and sat down by the phone. She dialed Ida, her close Mennonite friend and a good neighbor. The conversation would begin with calm chatting in English about green beans that needed to be picked and tomatoes that were ripening too slowly. Then, as if a valve was turned, the chatting switched to Pennsylvania Dutch. The volume went up. The words became accented with sprays of emotions.

The advantage of Dutch was that it kept other members of the phone’s party line from understanding messy details. Ida was the only one on the line who understood this odd dialect.

Talking to Ida may have helped her feel better, but it didn’t change the situation. She seemed to have given up changing the status quo.

I never spouted off to cows or talked Pennsylvania Dutch. I did become convinced that letting off steam was important. When you want to respond loudly and there are no cows or your neighbor is tired of your rant, then what? Can this energy be harnessed productively? Isn’t that what preachers do?

One time while doing the chores, my dad asked me what I wanted to be when I grew up.

“Either a farmer or a preacher. I like working the land and watching animals and plants grow.”

“Farming’s hard, heavy work.”

Dad didn’t respond to my thoughts on becoming a preacher. He knew both farming and preaching were nigh unto impossible for a Mennonite girl.

I thought the preacher was lucky to have the job of spouting off. He got to be loud about what was wrong in the world and how we could make a difference.

Impossible or not, I did dream.

I never thought much about writing as a way to let off steam or even as a way to share ideas. This changed. In college I became mad enough to write a letter. I had heard of plans for a reservoir in the fields across the road from our home. A large section of prime farmland would be destroyed. My letter helped spark enough response that the project was reconsidered and moved to a less fertile location.

I never considered English as a college major. I was good at art and math and that’s what I would study. I slipped in a poetry class. I loved it. Most of the time I felt my language was too Dutchy to be an English major.

A couple of friends tried their best at correcting my English. It was fine with me. I knew they liked me even when I seen things I should have saw and when I thought I was doing good in English even though I should have been doing well. It seemed like a day didn’t go by when one of them didn’t correct my English.

Years later, when we moved to Iowa, I was looking for something to do besides chase our energetic kids. I needed to find ways to use my brain. I missed the special after-school art classes I taught in Michigan. I missed the challenges of the active peace group. When I read that the Iowa City Press-Citizen was looking for people to add to their Writers Group, I thought, “Why not?”

Back then the Writers Group was made up of more than 20 community columnists. They would write 600-word opinion pieces on a regular monthly schedule. The topic was their choice.

My husband, not wanting me to have false hopes of selection, reminded me of my inexperience. Yes, I had written for the Hancock Food Co-op News in Michigan. Yes, I had written for the Copper County Peace Alliance Newsletter, but that hardly qualified me to write for a real city newspaper.

I prepared a letter. I carefully explained why the Press-Citizen needed me. They needed a rural voice that cared about the land. They needed a voice that understood Mennonites. I could bring a unique perspective. Much to my family’s surprise, the Press-Citizen agreed, and I started to write a monthly column along with press releases for the local peace group.

I had hopes of changing the world, but I soon found myself the target of criticism. I kept wanting to react. At the time I had a great editor who told me to get a tough skin.

I had stopped by the Press-Citizen’s headquarters to drop off an article, and he motioned me into his office.

He had noticed some comments my articles had received and wanted to be sure I wasn’t worried about the criticism.

“Jane, you’re not going to change their minds. If they respond, they have read your thoughts. You have them thinking and that is enough. Don’t waste your energy trying to change them. That’s not your job.”

“But I want to.”

He smiled, “That’s understandable, but use your energy to keep throwing out new ideas.”

This was good advice, although at times I was still tempted to answer some of the responses that my articles received. I seem to have an underlying desire to set people straight. Maybe it’s part of the Mennonite baggage that unintentionally teaches that we know better than the world, better than broader secular society. Maybe it’s part of having been a quiet child who missed all those chances to share my opinions.

Writing became like talking to the cows – words became mixed with the unpleasant smells of the world. Most of the time people didn’t respond, and problems didn’t get solved, but writing gave me hope. I was optimistic that as a society we could all care more, all see things we’d overlooked. We could have empathy that reached beyond our borders. Writing seemed more constructive than talking to cows.

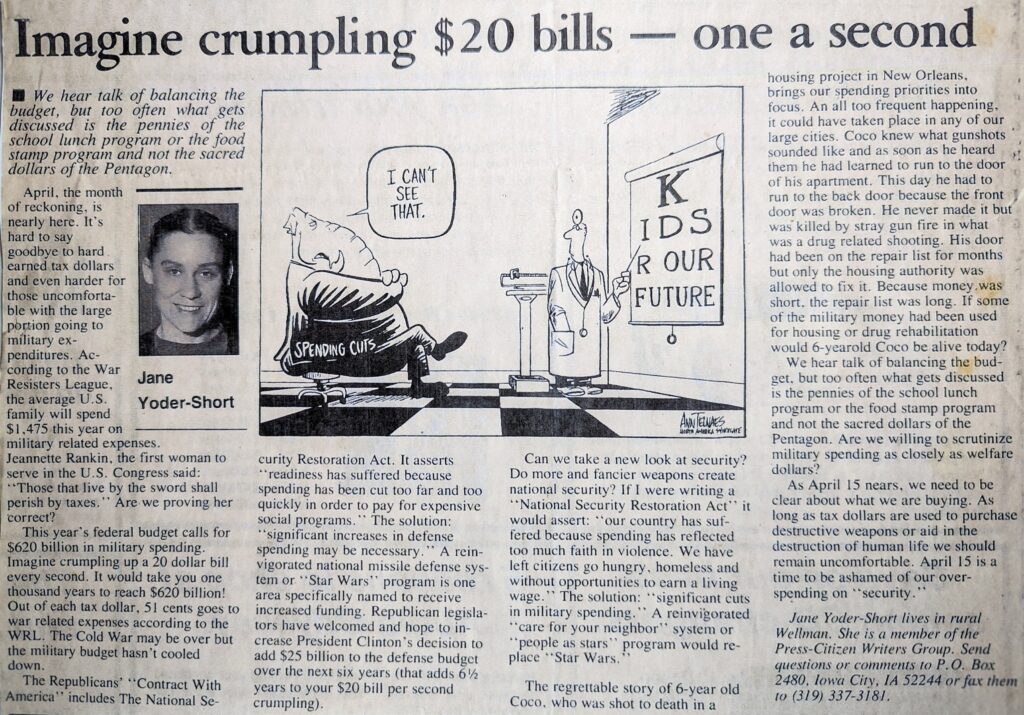

I continued to receive a wide variety of responses – some positive, others critical. I hadn’t been writing long until I learned which issues were hot-button topics. Writing about decreasing military spending was sure to get a rise. One of my first articles was in April when people were paying their taxes. I calculated that if you crumpled a twenty-dollar bill every second, it would take you one thousand years to reach 620 billion dollars, the military’s portion of our 1996 national budget.

Crumpling twenty-dollar bills earned me the title “Crunchy Granola Pants.” The person writing the response thought I was stuck in a hippie mindset that believed peace could be created through nonviolence. This was obviously unrealistic. I was told, “The world does not change through love but through power.” To think otherwise proved my crunchy granola pants status. My kids loved it.

“Hey Crunchy Granola Pants, can you help me with homework or are you too busy making granola?”

“How can pants be made of granola? Explain that in an article,” teased my daughter.

“What? I can’t play with paintball guns with my friends! You’re just a crazy Granola Pants Mom!” complained my son.

The name could have been a lot worse. I do like granola.

My topics and biases, like everyone’s, were colored by experiences. Ordinary lives can be rich with experiences and topics to write about.

My topics and biases, like everyone’s, were colored by experiences. Ordinary lives can be rich with experiences and topics to write about.

I wrote about CEO wages that were too high – drawing on my experiences as a factory worker. If you’ve ever sweated on an assembly line as the office managers toured the plant, you know there is a wage gap that no special Christmas party can wipe away.

The first factory that employed me taught me the importance of workers looking out for each other. A new employee, I didn’t realize they kept track of outputs on the presses used to bend and shape parts. I was bored and liked to see how fast I could go.

The buzzer sounded for morning break. We were sitting around the wobbly lunch tables when a kind older coworker pulled up a chair next to me.

She smiled in her usual friendly way and said, “Jane, you’re working too fast.”

“I’m bored and going fast makes time go quicker.”

“Let me tell you something. They keep track and pretty soon they will expect all of us to go as fast as you’re going. It’s okay for you when you work in the summer and then go on your way, but if you’re here long-term, fast isn’t so good.”

After our conversation, I slowed down, and more importantly I learned to see just a little better from the perspective of factory workers.

I continued to write about military actions, relying on my nonviolent biases as a Mennonite. Society’s belief in redemptive violence, and belief in military power as the way to solve problems, can go unnoticed unless you hear other stories. Biblical warnings about trusting in horses and chariots became linked to trusting in drones and smart bombs. Society easily ignores our violent systems of death and disaster. I tried to provide a small glimpse into the destruction connected to militarism in a way that made sense in a secular world.

I wrote about immigration, gaining from my experiences with migrant workers’ kids who were childhood friends. A farmworkers’ camp was located not far from our home. During harvest time, the workers’ children rode my bus. As someone who always stayed in one place, it was fascinating to hear about picking strawberries in Georgia before coming to pick tomatoes in Ohio. The image of my classmate Yolanda in an ICE border cage raised my inner pressure to its limit. No one deserved to be caged, regardless of their country of origin or their financial status.

I wrote about immigration, gaining from my experiences with migrant workers’ kids who were childhood friends. A farmworkers’ camp was located not far from our home. During harvest time, the workers’ children rode my bus. As someone who always stayed in one place, it was fascinating to hear about picking strawberries in Georgia before coming to pick tomatoes in Ohio. The image of my classmate Yolanda in an ICE border cage raised my inner pressure to its limit. No one deserved to be caged, regardless of their country of origin or their financial status.

I didn’t think of Yolanda as poor until she gave me an early Christmas present. Her family would be gone by then. It was a small wooden paddle with a small ball connected to it by a stretchy band. I excitedly showed Mom, demonstrating my ball-hitting talents.

“Look what Yolanda gave me. She is leaving soon and wants me to have it.”

“I think you should give it back.”

“No, she said she wanted me to have it.”

“She shouldn’t have given it to you. She is too poor to give things away.”

I negotiated with my mom. I knew Yolanda wanted me to have it. I didn’t give it back to her.

Thanks, Yolanda, for adding to my perspective.

I wrote about school prayer, reflecting on how my public-school years were a multi-hodgepodge mess where not everyone wanted to pray or even wanted to participate in the pledge of allegiance. School was not church and should not try to be. Some parents weren’t the praying type so why do their kids need to awkwardly help prove we are a Christian nation? On the opposite end, some Mennonites requested opting out of saying the pledge of allegiance. They believed their allegiance was to a different nation, a nation based on Jesus’s call to love. Pushing school prayer can leave a bad taste, like making kids eat the cafeteria’s Tuesday green bean casserole even when they hate mushrooms.

I recalled my third-grade teacher allowing some of us to pass on saying the pledge.

I recalled my third-grade teacher allowing some of us to pass on saying the pledge.

“I understand some parents don’t want you saying the pledge of allegiance but in my classroom, you will at least stand while the rest of us say it.”

I learned it is okay to be different.

I wrote about caring for dirt, earning me unsympathetic citations among farmers. Rumors had it that when I wrote about caring for the environment, I’d be mentioned at the local feed mill where the farmers hung out. One fellow relayed some of the conversations to me.

“Jane wants us to go back in time, maybe she’d walk beans with a hoe but I’m not going to.”

“I’d like to see her make a living farming without chemicals or subsidies.”

“She’s just a greenie liberal.”

I wrote about Native American rights, exposing my jealousy of a Michigan friend who had a small amount of Cheyenne blood in her ancestry and my sadness at our failure to admit to our connection to genocide and taking someone else’s land.

I wrote about Rush Limbaugh, as I tried to save the world from listening to the wrong radio show or at least tried to stop an acquaintance from frequently quoting Limbaugh’s “truth.” For some, Limbaugh was entertaining.

I carefully asked, “When is something mean-spirited, and when is it said in fun?”

I wrote about not buying stupid Amish kitsch, remembering my Amish relatives who didn’t look like the ceramic Amish salt and pepper shakers or the small cast iron Amish kids on a teeter-totter. This got a local tourist store owner informing me how she was “helping the Amish earn a living.”

Is it helpful to encourage Amish to sell their quilt-block hot pads amid chintzy clutter that makes fun of them? Who was making more money, the Amish crafters or the store owner?

Sometimes it seemed that I was stuck just seeing what was wrong with the world. Society can seem hopeless. Counter to my backlog of what is wrong with the world, I tried hard to throw in some positive, hopeful observations.

I wrote about the joys of Christmas shopping at resale stores, especially the Iowa City Crowded Closet where the profits went to the international relief, development, and peace work of Mennonite Central Committee (MCC).

It probably didn’t increase their business but maybe just noticing our shopping habits, even momentarily, was enough.

I wrote about moms who take foster children, sharing our Michigan experiences of newborn Joshy Squashy, as my kids called him, and first-grader, Brian.

Josh’s mom was 16 and couldn’t decide whether to keep him. I felt torn. Life isn’t simple. In the end, she kept him. At 16, I may have been good at nurturing animals but I’m not sure I could have handled motherhood.

Quiet Brian joined our noisy family. His favorite place was hiding behind the couch. We all find spaces where we feel comfortable. I had strict orders not to allow Brian’s dad anywhere near him. It did add a tone of fear to our household. Why was the car driving slowly by? Who was that on the sidewalk?

Brian’s mom had to prove she could be off drugs for an extended period. She wanted Brian back and she succeeded. I was happy for both of them.

In another article, I explained what went in an MCC Refugee Kit that included hygiene items such as toothbrushes and bar soap. I shared my memories of an older Ohio friend, who when confronted with a tooth-brushing chart in first grade, realized he was the only one in his class without a toothbrush.

He explained to me, “When I told Mom about our toothbrush chart, she told me not to worry. She would get me a toothbrush. Mom made me one with a rag and a stick. The kids in my class never knew what I brushed my teeth with.”

He explained to me, “When I told Mom about our toothbrush chart, she told me not to worry. She would get me a toothbrush. Mom made me one with a rag and a stick. The kids in my class never knew what I brushed my teeth with.”

I couldn’t imagine a family so poor they couldn’t afford a toothbrush.

Something as simple as a toothbrush, toothpaste, and soap can make a difference. Someone who has lost their home due to violence is left without basic supplies. We can all do little things that help make the world better.

I tried to have the article be hope-filled, not just let off steam on the unfairness of poverty.

After reading some of my earlier articles, I realized they were too preachy, too in-your-face. I got advice from an unexpected place, a woman who taught preaching.

“Think about it Jane, sometimes it is better to ask questions than give answers.”

“But it’s so tempting to shout the answers.”

She smiled.

It was tempting to simply let off steam, to assume my readers were not conversation partners but just there to listen. Eventually, I realized readers were not just cows to share grumbling with but instead were people whose experiences have led them to think differently. Readers who gave feedback taught me new ways of seeing. I saw that I could learn even when I was proclaimed wrong.

I tried to read a variety of news sources so I wouldn’t become too biased. It seemed like a worthy goal but then a friend told me, “You will always be biased, just be aware of where you are standing and the view you are taking.”

I admit it, I am biased. But hopefully, I can at least catch a glimpse of where I am standing and try to understand where others are coming from. And even occasionally rethink my biased presuppositions.

Writing for the Writers Group saved me from rural Mennonite smothering. Sometimes the Mennonite thing can become too centered on ethnicity. In theory, anyone can be a Mennonite. In practice, it can be hard if you can’t trace your Mennonite genealogy. Iowa Mennonite flavor has deep German roots and if you don’t know where Goldie Bender’s corner is or who Jake (pronounced Chake) Shetler’s fifth cousin is, you can feel left out. Non-cradle Mennonites, a rather derogatory label for those who don’t have Mennonite ancestral connections, are quite refreshing. They have actually chosen to be Mennonite, thus saving Mennonites from boring cultural predictability.

The Writers Group gave me a different Iowa perspective. The group was diverse. That’s what the Press-Citizen wanted.

In the beginning, the Writers Group gathered monthly at George’s, a bar in Iowa City. I liked to order a hard cider and remember my dad who enjoyed breaking open the spring cider barrel filled with fermented juice. Dad would have enjoyed chatting with this diverse group. I felt welcomed.

“What’s happening out in the cornfields, Jane?”

“Just quiet rumblings and nonstop hog smell.”

Crowded around a small table, amid the smell of beer, there was always something to talk about, whether it was the mistakes the Downtown Association was making, gun control, the Pride Parade, sports losses, street repairs, or university students’ crazy antics. I learned about the tensions between college students and locals and the tensions between Iowa City and rural Iowa.

I wrote what I viewed as secular articles, trying hard not to use pious words. I was surprised at how scrutinized I was by Mennonites. Was I giving them an unsavory reputation?

I’ve learned Mennonites have amazing ways of tracking you down. I received a letter from a person from my hometown in Ohio affirming one of my articles. He shared some memories of my family. Maybe Archbold was better than I had remembered.

The most amazing tracking came from a Press-Citizen article I had written on gun control. My daughter in Indiana asked me what I had written about guns.

“How did you hear about it? It just came out online. It won’t make print until tomorrow.”

“A friend in Kansas told me that someone in his church was upset about it. This person recognized my name as Mennonite and didn’t think Mennonites needed to speak against guns.”

“How did someone in Kansas hear about a Press-Citizen article in Iowa?”

“It seems you made a radio talk show in Virginia.”

“It seems you made a radio talk show in Virginia.”

“Virginia?”

I thought the original article was fairly low-key. I had included the story of our neighbor with his rather large, full gun case but even so, he and Dad got along. Dad didn’t like guns or want to go hunting. This neighbor ran a sports store that sold guns. If they could get along, why can’t we have a rational conversation about guns? Why can’t we talk about guns in a neighborly way?

I admit I am pretty stubborn when it comes to guns. I blame Mikey’s funeral. Mikey was a friend of my son back in fourth grade. Yes, I did include the story of when I took my son and three of his friends to that funeral. Mikey had found his dad’s gun. His parents found his brains on the wall.

That funeral will forever be etched in my mind. It was at a small church. You could smell the flowers surrounding the casket. Mikey’s parents sat in the front row. His mom sobbed and his dad sat stone-faced.

The four fourth-grade friends of Mikey next to me sat like zombies, staring forward all during the funeral. Even though they tried hard not to cry, I saw them wipe tears from their eyes.

The article included thoughts on Iowa’s proposed gun rights amendment to the state’s constitution. This amendment could end up dismantling Iowa’s existing background checks, concealed carry regulations, and permits to purchase. I proposed it is possible to talk about our differences. Maybe this is where the gun advocate thought my antigun rhetoric had gone too far.

I listened to what the Virginia NRA news host had said. He called my article “an antigun lecture.” And I was a “gun nut.” Somehow, I liked the “Crunchy Granola Pants” name better.

Our world has become smaller. Write something in Iowa and it’s talked about in Kansas and Virginia. It’s safer to talk to the cows where no one hears. Now even talking to the cows can get you in trouble. Someone could videotape it and post it and before you know it. you could be involved in an “ag-gag” violation. “Ag-Gag” refers to an Iowa law (and other states’ regulations) that forbid secret photographing or filming farm activities, particularly in big CAFOs – Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations, and their animal rights abuses.

We have a CAFO just a quarter mile from our Iowa home. It seems like a good article could be based on a conversation with some of these neighboring CAFO hogs.

“So, do you have any complaints?”

“Well, we never get to see any grass or even sunshine and it’s a little crowded.”

“But you do have plenty of food?”

“Yes, and we produce plenty of smelly manure to get back at humans.”

Enter an officer.

“What, I have to leave now? But I didn’t take any pictures. I was just visiting with the hogs.”

CAFOs and their smell have become an expected part of living in rural Iowa.

The smell of hog manure is a constant in our area. My ears understand and find it acceptable to complain about the smell of hog shit, but it’s another level to use it to describe a country. When a certain president called particular nations “shithole countries,” this crossed a line.

I was ready to shout about the viciousness of the label and the flaws of a person using those words. Steam had reached an explosive level. Instead of writing a column, I decided the Mennonite church I was attending needed to speak out.

This congregation included a family originally from Haiti, a supposed shithole country. We had a student from Mali staying with one of our families. We also had people who had lived, worked and taught in African shithole countries.

I composed a letter that I thought we could sign and send to the local newspapers, plus to our senators and representatives. The world should know that we don’t approve of derogatory names for other countries.

My letter went to a small group from the church. Mennonites believe in discerning together. Checking in with them seemed like a good process. It was decided to share the letter with the elders, four people who help oversee the congregation. One elder shared it with her spouse, and it was uphill after that. A special meeting with other church leaders and the pastor was called. This meeting ended focusing on why the letter I had composed was too political.

It seemed somehow that welcoming all nationalities, welcoming the marginalized, and speaking against racism had become political. I had assumed these actions were related to our faith. During the meeting I was fairly quiet, choosing my words carefully. I tried not to take the attacks on the letter personally.

Then it happened. One participant softly and piously said, “We just need to study the Bible and pray more.”

I thought this was directed at me. I could feel my pressure gauge rising. After the meeting, I lost it. I went outside and let off steam to the night frogs as I headed to my car.

I thought this was directed at me. I could feel my pressure gauge rising. After the meeting, I lost it. I went outside and let off steam to the night frogs as I headed to my car.

“What kind of faith is okay with countries and nationalities labeled as shitholes? When did speaking truth become simply political?”

Someone else modified the letter making it much kinder and gentler. The reports of derogatory remarks were described as reportedly made since some thought the name-calling never happened. There was no equating silence with overlooking injustice. There was no mention of standing against racism and hate, no mention of following Jesus’s way of reckless love. I, along with others, signed the modified version. I signed, but not without some mumbling and grumbling. It made the local paper.

I told myself to be thankful for the conversations that had happened, but I don’t always listen to what I have to say.

Sometimes messy situations occur, and we learn to step back and be more careful. Sometimes red beets end up on ceilings and we learn that letting off steam has to be done carefully. We hope we can learn as we clean up the messes. We hope that making a mess doesn’t prevent us from future attempts at facing explosive situations.

Copyright © 2023 by Jane Yoder-Short

Find granola recipes from Jane Yoder-Short here.

Jane Yoder-Short

Jane Yoder-Short grew up on a small Ohio farm surrounded by a Mennonite community. She was lucky enough to have Amish relatives. She keeps a little dirt on her shoes.

Yoder-Short holds a bachelor’s degree in art and math from Goshen College, Goshen, Indiana. She holds a professional bachelor’s in architecture from the University of Notre Dame, South Bend, Indiana, and a master’s in theology and ethics from Anabaptist Mennonite Biblical Seminary, Elkhart, Indiana.

Yoder-Short has lived in Indiana, Pennsylvania, the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, and now in Iowa since 1992. She enjoys writing as a way to share her thoughts and spout off. She is presently working on her memoir, Mennonite Farm Girl Stirs the Pot, A collection of untidy attempts.

Yoder-Short joined the Iowa City Press Citizen Writers Group in 2000 and continues to write monthly columns for them. She was a columnist for Mennonite World Review, an Anabaptist publication, from 2010-2020.