By Amy Kolen

Chapter 6

Standing by the piano in my living room, I struck middle C, to confirm my first note before running through one of my voice teacher’s warm-up exercises. I was trying to inhale at the beginning of each phrase, filling my body with air from the bottom up, remaining relaxed and controlled, as he instructed, supposedly imparting a freedom to my breathing and a sense of direction to the phrase. This particular exercise added different vowels to the consonant “M,” as I traveled up and down the scale.

Standing by the piano in my living room, I struck middle C, to confirm my first note before running through one of my voice teacher’s warm-up exercises. I was trying to inhale at the beginning of each phrase, filling my body with air from the bottom up, remaining relaxed and controlled, as he instructed, supposedly imparting a freedom to my breathing and a sense of direction to the phrase. This particular exercise added different vowels to the consonant “M,” as I traveled up and down the scale.

“Ma,” I sang, trying to keep my vowels open. “Mamamama.” I ran my fingers down both sides of my face to feel the tallness, as Mary advised us during warm-ups in choir. “Mamamamama.” I challenged myself to go as high as naturally comfortable without pressing, and then without warning my eyes filled with tears.

I never called my mother Mama. That’s how she referred to her own mother—a rarely smiling Russian immigrant who seemed to me, even as a child, to carry a heavy sadness. My mother used to phone her from Iowa every two weeks. “Mama? Mama?” My mother’s voice rose on the second syllable when my grandmother, over one thousand miles away in Queens, New York, finally picked up the receiver. “It’s me, Mama, Lily.”

For months my mother’s family of origin had superseded, in what was left of her mind, the family she’d created with my father. Sometimes she asked me who was taking care of the children. Since my niece, Jessica, had recently visited from her home in San Francisco with her infant daughter, the first time Mom asked the question, I answered, “Jessica’s taking care of the children,” not realizing that my mother’s interest in the present and any connection to a future had faded. “Not Mama?” my mother had said, becoming agitated. “Where’s Mama? Where’s Mama?”

When she panicked, my mother’s voice, a monotonous drone since her stroke, became breathless, almost like panting. She could catapult from anxiety to panic quickly, and at such times, I longed for the intervention of one of the two music therapists (MTs) who visited her regularly in the Health Center. As a hospice patient, my mother received music therapy as part of the program, and I’d also hired a private MT who came once a week. What these golden people accomplished was magical. Everyone in the Health Center, from nurses to social workers to the rabbi of our local synagogue marveled at my mother’s short-lived, but real transformation during the MTs’ visits, and I’d witnessed the alchemy on multiple occasions.

“We process music in our limbic systems,” one of my mother’s MTs explained, “and our music memories are linked to our emotions.” Along with helping my mother to relax physically and mentally, each MT worked toward nonmusical goals by providing live music that my mother wanted to hear “for pain management . . . and as a stimulus for life review, mood elevation, and as an opportunity for her to exercise choice and autonomy.”

Even when Mom couldn’t speak without crying, the MTs could often animate and distract her through the power of their music and sensitive attention. Mom loved June’s red guitar and her voice. During my mother’s last Hanukkah, when her face seemed frozen in a grimace of pain and she cried more often than not during her waking moments, I gave June the names of some holiday songs my mother might recall. With tact and good humor, June encouraged her movement of breath and body, and got her to connect with her body to the extent she was capable, sitting in her wheelchair and propped up with a pillow on one side. She knew Mom needed to stay calm and kept her both soothed and energized.

“I have a little dreidl. I made it out of clay.” June’s sweet soprano filled my mother’s small room as she strummed the beginning of “The Dreidel Song,” a piece I used to sing as a kid. Mom’s eyes were closed, but her feet tapped lightly on the floor. I joined my voice with June’s, and following her lead, kept the tempo slow, so that Mom might more readily sing, if she remembered a word or two.

“And when it’s dry and ready, then dreidl I shall play.”

“I shall play.” My mother’s eyes remained closed but she’d vocalized the last part of the phrase, “I shall play.” She wasn’t singing the F major chord, with which the song opened, but June quickly adjusted her range to the one my mother approximated, and boom—Mom was off and running. She didn’t sing every word in each of the three verses, but she hit every “play and spin” and “dreidl, dreidl, dreidl,” and after each verse, June leaned in close to Mom’s body, gently clasped her good hand, and murmured praise. Then she moved on to the next song. In the quiet after my applause, generated from a particularly rousing rendition of “S’vivon,” when my mother even shook the maraca that June had eased into her hand, Mom laid the maraca across her lap and began tapping her palm against her thigh.

“This is the only way I can clap now,” my mother said. “My other hand doesn’t work anymore.” She raised her clenched left hand slightly off the wheelchair’s armrest by bending it back a little at the wrist. “Can you hear me clapping?”

“Loud and clear, Mom.”

“You’re doing great, Lillian.”

My mother closed her eyes and smiled.

Listening to music that we enjoy releases dopamine, one of the feel-good chemicals in our brain, even one as damaged as my mother’s. And singing, alone or with others, even using vocal cord tissue that’s been around nine decades and has become thin and inelastic, like my mother’s, releases the hormone oxytocin, what researchers call “the bonding hormone,” and “a brain tool for building trust” that’s important for healthy nerves.

Aware of my mind and body’s positive response following prison choir rehearsals, voice lessons, and practicing on my own, and wanting to dim the importance of possible external cyclones in the Health Center when I visited my mother, I tried to schedule my time with Mom directly after my lessons. Or I ran through choir scores, scales, and other exercises at home, swooping my voice from low to high and down again, like a siren, before seeing her.

Though her stamina and mood were often low, she clearly got a quiet rush from musical interludes with her MTs in a day that was always too long for her. And when she became upset, like the day she perseverated about my father after various nurses had given her different information, in response to her question about her dead husband’s whereabouts—“I want to find my husband! He was here with me yesterday! Where’s my husband?”—June didn’t encourage her to remember that my dad had died or corroborate one of the stories a nurse had told her, which would’ve aggravated the situation. Instead, she met my mother where she was, in her agitated state, and led her out of her distress, matching my mother’s anxiety with music, gradually decreasing the tempo and complexity of the songs to ease Mom to a more comfortable state.

“Moon River, wider than a mile, I’m crossing you in style, some day.” My mom mouthed the words along with June’s singing. Between “Oh, What a Beautiful Morning” and “Sentimental Journey,” two aides transferred my mother to her bed in prep for her morning nap, and after the latter song, Mom described to June some of the countries where she and my dad had traveled and lived (Scotland), including countries they’d never been (Italy, France, and Ireland). “I have pictures of all these places,” my mom said, waving her good arm in the air, as if to indicate pictures she thought were on the wall by her bed. “See?” June said the images (photos of various family members I’d framed and hung on the wall a week earlier) were lovely. Five minutes later, when we both slipped out of her room, my mother’s eyes were closed and she was softly snoring.

My mother’s ninetieth winter slipped to spring in the Health Center. She didn’t realize that the sixth-floor apartment she once shared with my father was no longer hers. She had no idea that my brother, on one of his visits from Ohio, and I, along with help from my nephew Sam, from Seattle, had divvied up its contents, easily dividing what we considered important and designating everything else for Habitat’s ReStore. She didn’t know that I’d cleaned out her final independent living place and returned the key to Oaknoll’s main office, that the Health Center was her permanent home now.

My brother and I were fortunate that our parents bought into the lifecare community Oaknoll provided, which gave them unlimited access to fulltime nursing care when they needed it. We were fortunate Oaknoll’s Executive Director had been patient and understanding. Mom’s apartment had been vacant for about six months before I relinquished the key. My brother and I had been lucky, in general. We never had two parents in a nursing home situation simultaneously. Decades before our parents moved into Oaknoll, when our father’s autoimmune disease, Scleroderma, flared and he needed medical help outside of the hospital, our mother took care of everything at home, and even drove Dad by herself—she never liked to drive and had a poor sense of direction—the two hundred miles from Ames to Rochester’s Mayo Clinic for a firm diagnosis, rejecting my offers to help chauffeur.

We were lucky our mother was never on what Intensive Care and Palliative Care physician Dr. Jessica Zitter has called “the end-of-life conveyer belt.” Staff in the Health Center and Mom’s physicians knew she didn’t want to use heroic measures to prolong her life, that she didn’t want a “mechanized death.” She was never on a ventilator, never had feeding tubes, artificial nutrition, or hydration. The nurses believed in “de-escalating life-prolonging procedures”—including not giving flu or pneumonia vaccines. We were never fearful of losing our life’s savings to help cover her medical expenses, because our parents had ensured they’d have enough money for long-term health care. We were always able to connect with the social workers in charge, who apprehended my distress and our mother’s, and though most of the CNAs were overworked, they always engaged with me and answered any questions I had. Not once in those fifteen months post-stroke did I receive anything but compassion and appreciation, which felt like love, from almost everyone caring for Mom.

I’d wanted, even expected my brother to visit more often than the few times he’d managed after our mother’s stroke, as such visits provided tremendous morale boosts for me. But I came to realize—as I eventually realized that my need for emotional intimacy with Mom was not her need—that my wanting my brother to be with me and our mother was my desire alone. At the same time, I considered myself fortunate that he agreed with my decisions regarding the primary goal with our mother’s care: keeping her as comfortable as possible.

When I’d opened her apartment for the last time, rock-hard toast lurked in the toaster oven, shrunken oranges puckered in a bowl on the counter, mold glistened on barely covered jars of pickles and jelly in the fridge, clothes left in the washer exuded a pungent, mildewy smell. And without warning, images surfaced of entering my in-laws’ apartment, eighteen years earlier, after the car accident that took their lives. Underwear in the dryer, kitchen table messy with crumbs, coffee grounds and breakfast remains in the sink, bed unmade. They’d planned to return home right after lunch at their favorite Japanese restaurant. And I remembered thinking then: if the life that I’d intended to return to was broken off abruptly, the sheets and covers on my bed would always be neatly arranged, my dishes washed, laundry folded and put away. I didn’t want anyone coming into an unkempt house.

When I emptied Mom’s small writing desk, though, I was happily surprised with both poignant and delightful testaments to her hidden inner world, and also evidence of her mind failing. Inside the top center drawer was a folded piece of paper with a meal menu from the Oak Dining Room on one side. On the other side, in my mother’s handwriting, a script for what she’d order for dinner and have delivered to her apartment each day that week. The entry for Monday, a week before her stroke: “I will have the baked salmon and I will have a side of French fries and a side of cottage cheese. I will have skim milk and coffee to drink. I will have no dessert.”

Complete sentences, with articles included, no contractions. Though the letters of each word were generally vertical, as she always formed her letters, and legible, they weren’t uniform in size, as was typical for her, and they drifted a bit to the right, as if sliding off the page.

That piece of paper confirmed what I’d wondered for some time: All the small strokes (TIAs) that she’d denied for years had probably impaired her ability to converse and think without prepping. For at least a year leading up to this major stroke, I’d found it almost impossible to talk to her, especially on the phone. She’d answer my “how are you?” with a single monosyllabic “fine,” and then, after a long pause, ask the same robotic questions she always asked: “How are you? How is Michael? How are the kids?” If I tried to relay any information other than “fine,” to which she’d always reply, “good, good,” I’d be met with silence. Frustrated, I’d try to prompt her: “Are you still there, Mom?” “Yes.” “Did you hear me?” “Yes, I heard you.” “Then why don’t you say anything?” No response. I hadn’t asked her a yes/no question.

Under the menu were two small notebooks. One revealed, in my mother’s familiar cursive, lists of authors and books: Carl Friedman, The Shovel and the Loom; Cynthia Ozick, The Messiah of Stockholm; Anita Brookner, Falling Slowly. Pages of book lists, interspersed with words and their definitions and sometimes the diacritics and accent marks to aid in pronunciation; poetry excerpts; quotes by multiple writers, including Chinua Achebe, about the importance of family; May Sarton, about the comfort of a good friend; a quote from Agudas Achim’s bulletin that the rabbi had reprinted about the blessedness of human touch; a list of “to-read” books; “random thoughts” that I assumed she’d generated because she hadn’t attributed them to anyone: “Depressing is when your phone is out of order for 48 hours and only you know it.”

The other notebook yielded Nancy Mairs: “You never know what you can do until you have to do it,” Margaret Atwood: “the past is a great darkness and is filled with echoes,” Sogyal Rinpoche: “…belief has little or nothing to do with reality. This make-believe, with misinformation, ideas, and assumptions, is the rickety foundation on which we construct our lives.”

I also keep small notebooks in which I record words and their definitions, quotes and poems that I want to remember, books I want to read. So much that my mother read and wanted to read! So many of her writers favorites of mine! I studied the pages in front of me—pages I could access only because my mother would never see them again. What if we’d read these books together, in a book club of two? We might have had lively conversations, our relationship possibly deepened, if only she’d opened up to me, talked to me. That fantasy lasted only briefly before I recalled a comment Mom made over four decades earlier to a friend of hers and the confusion on her friend’s face in response. The friend’s daughter was a young undergrad, as I was then, and the woman was relating how she never had a chance to talk to Lucy, home from college on vacation, because Lucy was so busy. Mom had shrugged. “Talk to her? Why would you want to do that?”

From Anne Truitt’s Daybook: The Journal of an Artist, which I’d given her, but didn’t know she particularly liked, she’d highlighted “. . . when we love one another the most delicate truth of that love is held in the spirit. . . the love is fixed, instantly accessible to memory. . .”

What is instantly accessible to my mother’s memory now? She only occasionally remembered who I was, and though our children, Raychel, in Eugene, Oregon and Daniel, in Chicago, visited when they could, she’d generally forgotten who they were, only vaguely placed Daniel, as “someone’s grandchild.” Once she asked me about “my new son, Reuben,” actually my friend Julie’s child. Julie helped my mother eat lunch on Mondays and had told Mom about Reuben, recently returned from his army stint in Afghanistan.

She remembered the act of writing, though, and reading. One afternoon when I was in her room and writing a note to her social worker, I glanced up to see her looking at me. “You write so quickly. I used to be able to write,” she’d said, without a trace of self-pity, marveling at my dexterity with a pen. “And read.”

Did she recall the poetry that she’d written for decades, commemorating family events—births, anniversaries, graduations, awards, new puppies, Dad’s new dentures—and what she called “light verse”? Her poem, “The Cow” was published in Lyrical Iowa, 2005:

Science has its funny ways

To get inside my rumen maze

With cannula and fistula

It probes my dreary viscera

This is done for science’s sake

But it gives me a stomachache!

A social work intern in the Health Center collected all the poems I could find, copied them, and arranged them in a binder titled “Lillian’s Book of Poetry.” In smaller font under the title, she’d typed a gentle suggestion to my mother’s companions and nurses: “Please feel free to read these with her.”

Some of the people caring for my mother got glimpses of her occasional whimsical side before she stopped communicating with words. After one of her aides gave her a manicure, applying green polish to her nails, my mother had me wheel her up and down the Health Center corridors, the fingers of her hand that could still move splayed out in an arthritic version of jazz hands, as she chortled to anyone within earshot, “Look at me! Look at me! I have green thumbs!”

Another aide, Doris, who called Mom “her lovely Lillian,” found my mother “charming and feisty” when she said things to her that would’ve had me climbing walls.

“You ate less bites of the peaches than you did yesterday,” Doris said to my mother after lunch one day.

“That should be fewer,” said Mom. “I had fewer bites than yesterday. Use fewer when you can count the nouns and less when you can’t.”

Rather than getting irritated, Doris just laughed, and she repeated that story to others, always with good humor. “That Lillian,” she’d say. “She’s got so much spirit!”

Most of the people caring for my mother, though, didn’t see her as particularly endearing and weren’t aware of her accomplishments. They didn’t know, for instance, that she’d been a talented, prolific knitter of sweaters, for herself and others; that she’d constructed plaques from postcards of her favorite paintings (which she’d glued to rectangles of wood my father beveled on his circular saw), varnished, and sold in a local boutique. They hadn’t eaten her perfectly moist banana bread, almond cake, or buttery, fruit-filled rugelach and turnovers, treasured by all fortunate enough to taste the confections. They weren’t privy to the quaintly rhymed poems she and her friend Lois wrote to each other on handmade cards for birthdays, anniversaries, and in thanks for any number of favors. I brought in as much of my mother’s previous life as the space in her room would hold. I wanted anyone who entered that room to get a sense of the person she’d been—infuriating for me, to be sure, but able-bodied, well-read, intelligent, and playful, in her own way, as evidenced by her poems.

I’d never seen my mother draw or paint. To the extent that she was up to it, though, the rec therapy aides tried to get her to communicate, using crayons, watercolor markers, and colored paper during her weekly sessions with them. Although Melanie actually created the images signed “Mom,” the sentiments behind the rainbow-hued arc bearing my name suspended over the line drawing of a figure with long, dark, curly hair and the words “To Amy Love Mom” were clear, though my mother hadn’t voiced such feelings to me since I was very young. As were the emotions behind the scrap of blue paper with a smiling frog sticker and Hershey Kiss taped to it and the words, “Bright and beautiful and a precious sister” that my mother “made” on Kindness Day. She’d intended this offering for Beatrice, but the aides figured it was for me.

Melanie attempted to represent what she thought my mother was feeling or what she thought my mother was supposed to be feeling, but nobody really knew what her innermost emotions were. Flipping through these pieces of paper with their simple images in bright primary colors propelled me back to childhood, when I’d churned out picture after picture, giving each one to my mother, who’d praised me, adding each drawing to a pile that she kept on a shelf in the living room cabinet. My mother allowed me to feel visible then, as a young child, like I had something valuable to say. I thumbed through the pages bursting with color and light from the rec therapy aides. Maybe my mother was saying that she wanted to be heard, that she loved me and appreciated that I was in her world, even if she was channeling her sentiments through Melanie. More likely, though, my interpretation of those pages stemmed from a deep, ever-present longing for an intimacy with my mother that could only ever be a fantasy, like the one I briefly conjured around our book club of two.

_________________________________________________

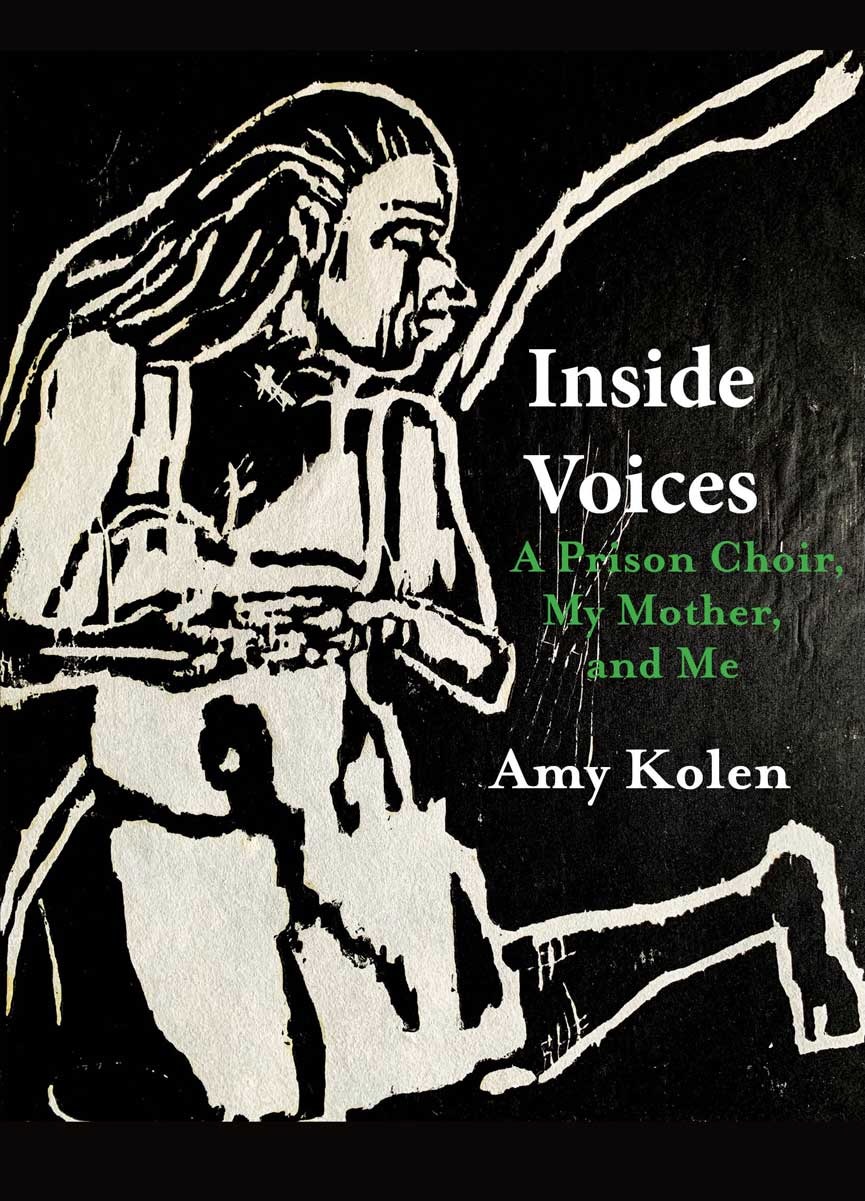

For fifteen months Amy Kolen traveled between two very different worlds: a medium-security men’s prison, where she participated as an outside singer in the prison choir, and the confines of her mother’s room in a health center, where her mother required round-the-clock care following a massive stroke. The author realizes the limits of her turbulent relationship with her mother, Lillian, while navigating her new role as an initially reluctant advocate for a woman with a diminished voice. At the same time, she welcomes the community within the prison walls as a place of acceptance and freedom. Working with the inside singers provides the expanding perspective she needs to approach her mother in a new light, eventually finding self-affirmation, clarity, and grace during the final fifteen months of Lillian’s life. Told with unflinching honesty, Inside Voices speaks to our longing for human connection and is a testament to how embracing new experiences with a “beginner’s mind” can deepen understanding and bring inner peace. (from Ice Cube Press)

This excerpt is Chapter 6 of Amy Kolen’s Inside Voices: A Prison Choir, My Mother, and Me, released recently by Ice Cube Press. This chapter is printed with permission. Click here to order a copy of Inside Voices.

Copyright © 2025 by Amy Kolen.

Photographs courtesy of Amy Kolen, Raychel Kolen, Allen Kraft and Janine Calsbeek, Ri Butov on Pixabay, and Jean Carlo Emer, mk.s, Bruce Tang, Olga Dudareva and Annie Spratt on Unsplash.

Amy Kolen

Amy Kolen’s book, Inside Voices: A Prison Choir, My Mother, and Me, was released recently by Ice Cube Press. Kolen’s essays have been published in several anthologies, including Best American Essays, 2002. Her work has also appeared in various publications, including Orion Magazine, The Missouri Review, Bayou, The Massachusetts Review, and The Florida Review, and has been shortlisted in Best American Essays, 2009. Holding an MFA in Nonfiction Writing from the University of Iowa, she sang with the Oakdale Community Choir for four years. She lives with her husband in Estes Park, Colorado.

Click here to read more about Inside Voices or to purchase a copy.