I grew up in Milledgeville, a little town of about 1,000 folks in the northwest corner of Illinois. My village lies on the very edge of the Driftless Area and looks more like Iowa or Wisconsin than what many people think of Illinois. There were lots of farms where country people raised livestock, and row crops to feed their animals – not so much to sell the grain.

I grew up in Milledgeville, a little town of about 1,000 folks in the northwest corner of Illinois. My village lies on the very edge of the Driftless Area and looks more like Iowa or Wisconsin than what many people think of Illinois. There were lots of farms where country people raised livestock, and row crops to feed their animals – not so much to sell the grain.

My mom and dad worked as tenant farmers or hired hands to have housing provided so they could save money to buy their own home. My dad was also a full-time cheesemaker, producing Swiss cheese for Kraft. My mom worked full-time running the household.

After leaving home, I led a nomadic life. When my mother passed away in the late 80s, I travelled back to Illinois from the Pacific Northwest to help my dad. That first night back home, I went up to my old room to sleep.

Before I turned in for the night, I opened an old hope chest to see what might be inside. There were lots of photos of our family and various bits of memorabilia. And there was a box marked “Becky’s Stuff,” in my mom’s handwriting.

Inside was another little box, the original box of a pair of baby shoes, along with my christening dress, my bonnet, one bootie, a lock of my hair from my first haircut and my mother’s senior yearbook.

And there was a folded-up piece of paper that said, “Butchering Story by Becky.” I wrote that story when I was 13, through the eyes of my four-year-old self. I would like to share that little story with you.

“The Butchering Story” by Becky

I’m not really sure just what woke me that morning, I thought it was a gunshot or two. At 4-1/2 years old, I was pretty sure what a gun sound was like.

My dad did a little hunting in the ditch across the field in front of the house for rabbits, pheasants and an occasional squirrel. However, the discharging of firearms not being a regular occurrence, out of my warm bed I jumped. I raced down the long hall of our cold old farmhouse to get a peek at what was happening.

I grabbed my one-step stool from the bathroom (the one I used to reach the sink to brush my teeth) and placed it on the floor beneath the round window at the end of the hall that looked north toward the barn. Through the mist and fog of that cold morning – it was fall or spring, I can’t recall – I saw what explained the shots.

I saw my dad, our landlord HH, and his father, HH senior, a spry old man of about 80. They had a fire going under a large black pot that was steaming. On either side of the pot were two crisscrossed poles and another large pole across the top, joining the two.

The three men were tying up something on the ground. As I stood looking through the window, I saw my dad throw the rope over the pole and the three of them started pulling a big dark something up off the ground. The sun was starting to rise a bit over the horizon by now, carnival pinks and blues. The dark black mass, the big dark something, started twisting on the rope and revealed its silhouette. There was no mistaking the shape, the ears, the snout.

It was Blanche, the pig.

The other dark mass on the ground was W.C., her pal in the pig pen.

This scene I looked at, on this cold morning in Illinois, as a child of four or five, did not frighten me or make me sad. Blanche and W.C. came home with us as piglets, from HH’s farm, riding on my brother’s and my laps in the back of my dad’s ’55 chevy. We knew from an early age that any animals we fed, with the exception of our dog Duke and the barn cats, were fair game for the dinner table.

But prior to this, it had been chickens or ducks, neither lovable creatures, and never anything this BIG! I returned my one-step stool to the bathroom, gave a quick brush to my teeth and headed downstairs.

In the kitchen there was a great deal of activity. My mom and Mrs. HH were cooking up sausage, bacon and ham. In a cast iron skillet on top of the wood stove were cottage fried potatoes keeping warm. There were biscuits, cornbread and my mom’s cinnamon rolls and they were starting to mix up enough eggs to feed the town.

They were oblivious to me, except for old Grandma H. She was sitting near the stove, smoking a pipe and dressed in her usual attire of men’s clothes. She was scribbling notes on paper. She had wonderful blue eyes, like you might see on a wild horse or dog. She had whiskers too, but they were soft. All that combined with the sweet smell of her tobacco and her indifference to what was expected of women at that time, connected us. At our first meeting, we were friends.

Knowing at this point, save for her, that I was as invisible as a ghost, I got into my outdoor clothes and headed toward that steaming pot over the fire. They saw me coming and my father called out that I should not be a bit concerned at the carnage I would see. The others stopped in their tracks. They had no idea how experienced I was at slaughter. I had watched my dad behead chickens and ducks.

After the initial shock that morning, along with a calming slice of sugar bread, I was all in.

My dad started giving me directions. And asking questions. “Does your mom have the basement ready, did she bleach it down? Ask if there are enough shrouds and is that darn cat and her kittens still down there? Becky, you go move them to the barn.”

Priscilla, the new mom of six little kittens, got moved. My brother, still sound asleep upstairs, didn’t notice that a family of seven had taken my place in the bed. He just yawned and curled toward the warmth.

I was hungry and down in the kitchen, there were suddenly an awful lot of people.

When I finished reading the story that night, I folded it carefully and put it back in the box. I shed some more tears over the loss of my mother, but also smiled because she had put that little box together for me.

When I finished reading the story that night, I folded it carefully and put it back in the box. I shed some more tears over the loss of my mother, but also smiled because she had put that little box together for me.

That box, “Becky’s Stuff,” went back to Oregon with me and made at least four cross-country moves. It went with me from my first marriage to my present one and did more traveling. It was always the first thing I packed and the first thing I unpacked, to put it in safekeeping. I read the story to my husband a few years after we were married, and he has been pestering me ever since to share it with others. I guess he finally got his wish.

Thanks so much for listening.

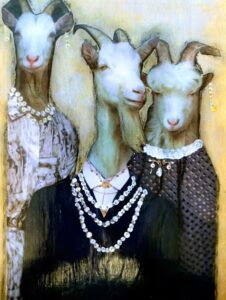

Artwork by Rebecca Hawkins Valadez

Photo of items in the box by Rebecca Hawkins Valadez. Photo of Rebecca by Sal Valadez.

Copyright © 2023 by Rebecca Hawkins Valadez

Rebecca Hawkins Valadez

Rebecca Hawkins Valadez was born in the mid-fifties in southwest Carroll County, Illinois in a small agricultural community, Milledgeville. Her parents were not farmers, but she has had a lifelong fascination with livestock, horses and chickens.

She spent her young adult years roaming the U.S., doing everything from waitressing, cooking for wealthy folks and running a food cart to raising sheep, grooming horses and working as a deckhand on the Columbia River. In Normal, Illinois, she opened a restaurant and art gallery with her first husband. Later she continued with the cafe, married again and at age 42, began college – studying art, anthropology and early childhood education. She worked in bilingual special education until 2009 when she was diagnosed with lung cancer. After surgery and chemo, she was told to get her affairs in order. Fifteen years later, she is still healthy and thriving.

Her visual art, stories, percussion and puppetry are inspired by her lifetime of observation.

Rebecca and her husband Sal live in southern Illinois with two dogs, and are currently rewilding their yard to native prairie as a sanctuary for birds, native bees and monarch butterflies. They spend their leisure time roaming the bluffs and the American Bottoms.

Her visual art is currently represented by Main Gallery 404 in Bloomington, Illinois.