“We’re almost there,” said my father.

He liked to drive long distances with his left arm resting on the open window, making it always a shade darker and more freckled than his right. An autumn wind blew across our faces and the rich odor of pig manure mingled with road dust in the air. It was Labor Day, 1963. We had just traveled from Madison, Wisconsin, across the Mississippi, into the heart of Iowa farmland. The three-hour trip had been mostly silent. My father wasn’t one to talk much to his children. I was the only passenger – which was unusual – and sitting in the back seat I felt slightly uncomfortable. My older sister Laurie would have been with us, but she was coming in from another direction after spending the summer with her boyfriend, working at a camp in Pennsylvania. My mother, normally the front seat passenger, remained home with my twin brother, who would not be starting high school this year. He had developed more slowly because of difficulties with our premature birth and was held back the year we were to start first grade.

Sarah was my friend and peer in this adventure, but she wasn’t here either. We were the same age and had seen each other at First Day School every Sunday morning since my family moved to Madison when I was five years old. “First Day” is Quaker-speak for Sunday. The adults in our Meeting took turns leading us in character-building activities. We learned about the “inner light” and social justice. “There is that of God in every person,” they all said, one way or another. Last year, to demonstrate the equal worth of all people and expose us to the diversity of religions, we visited a different church denomination each week. Questions seemed more important than answers, and there was no rigid Biblical dogma. Quakerism was not necessarily taught. It was to be communicated by example.

I had liked it best when Sarah’s father was in charge of First Day School. An animated soil science professor, he would play his violin and teach us songs about the earth that were mostly devoid of words like sin, soldier, or Christ. Sometimes he would organize us into puppet show productions that were folk tales – parables of right behavior – that usually ended with the kids, the audience, and the puppets all singing and laughing. Our families were friends, and sometimes on Sunday afternoons we would have dinner together. We met at the reasonably-priced cafeteria at the University Student Union or at their house on the Yahara River, often eating oven-heated Swanson chicken pot pies, a favorite of Sarah’s.

Her parents admired my father and his grand work to make the world better, but they had concerns about his driving. They had decided to drive Sarah separately. It was true that Dad was now more than seventy years old and had an essential tremor that made his hands shake uncontrollably, but I had never known him to have an accident. Drinking a cup of hot tea was more problematic for him than driving, and we’d hold our breath as the scalding liquid sloshed back and forth in his cup along the jerky trajectory to his mouth. The tremor seemed normal to me. I had never known him without it.

As soon as the car turned south off the paved Herbert Hoover Highway, gravel crunched beneath the tires, slowing us down and throwing more dust into the pungent air. I’d been mesmerized by the changing landscape the entire trip, only occasionally glancing at the back of my father’s close-cropped head and his ears that seemed abnormally large. I didn’t learn until years later, that all human ears continue to grow until we die.

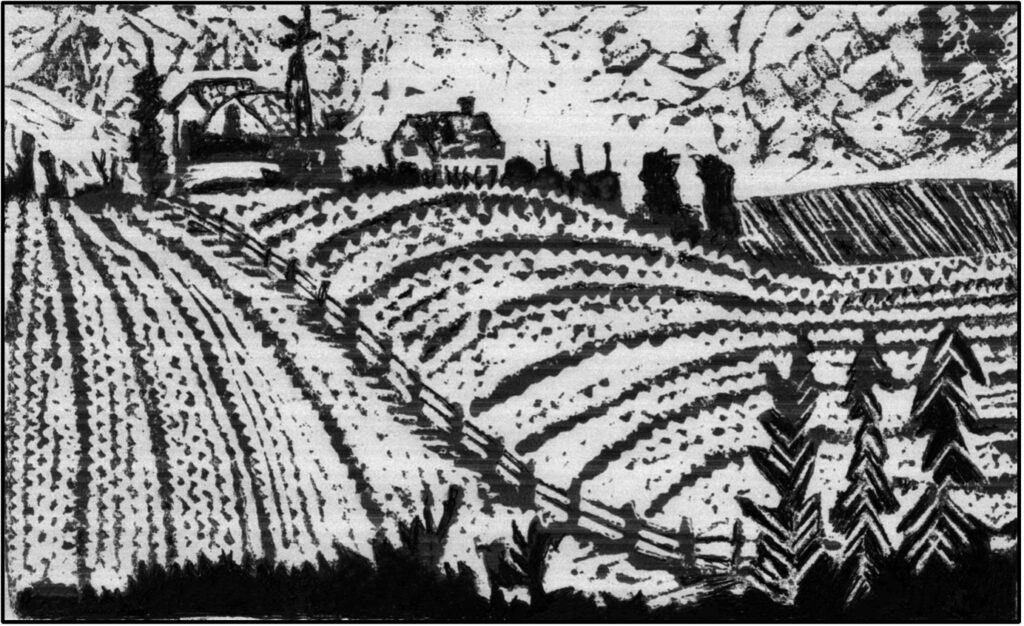

The one-mile grid of roads in Iowa contrasted with the familiar asymmetrical and diagonal city streets I’d grown up with in Madison. There the roads went in all directions and randomly bumped into curvilinear lakeshores. Here the world was orderly. For miles, furrowed rows of corn and soybeans followed the slight contours of the rolling land, but mostly held to the dominant right-angle grid pattern established by the roads. Crop row lines came into focus as we passed by, then disappeared into the larger shape of the field. The undulating simple forms eased my mind.

Rural Iowa was not totally unfamiliar. During several hot, humid summers, we three children had spent a week with our adult half-sister Martha and her family at their farm near Cedar Rapids. Our days were filled with the magic of riding the pony, leaping in the hay mow, and exploring the wild, uncultivated ditches where we built grass huts for a litter of kittens. We witnessed a cow sacrifice her life, as the farm vet, arm-deep in her body, pulled out a wet calf. To our horror the bloody process appeared to turn her almost inside out and a bullet straight to the brain relieved her suffering. Martha’s husband – our brother-in-law, the farmer – had read Shakespeare in school and named the wobbling new orphan McDuff, a character who had also been ripped from his mother’s womb. We took turns feeding the long-legged creature warm milk from a pail with an oversized rubber nipple, steadying ourselves while he forcefully sucked and butted us. Sometimes we ventured down the endless rows of tall corn in the fields until our fear of getting lost overwhelmed us. At night we retreated into the stuffy farmhouse to sleep, grass and straw sticking to our sweaty skin.

Now, Dad and I were nearly there. Ahead on a rise, I could see our destination, just beyond a field of tall corn that had already started to turn brown awaiting harvest. Through a row of long-established cedar trees that flanked the road, an eclectic grouping of buildings became visible. I could see a flat-roofed split-level 1950s modern brick building sited above a large expanse of mowed lawn that formed a sort of grassy basin. A stately maple tree grew in the center, and a weeping willow at the lower end, close to the road that we drove on. The view seemed almost like a movie set dropped into the agricultural landscape, with a windbreak on all sides to provide protection from the midwestern winds.

“This is it!” I thought, my heart thumping.

I was fourteen, and had finally started my menstrual cycle, later than most of my friends. My teeth felt smooth to the tongue and finally straight, after years of wearing sharp metal braces with annoying rubber bands. I was on the threshold of a life change. Deep in my chest was the ache of sadness about leaving my faithful collie Shay and school friends, but I also felt the tingle and rush of anticipation at the edges of my body.

We approached the entrance driveway. A simple white sign hung from a post at the corner, with hand-painted black letters that read:

Scattergood School

Scattergood is an accredited coeducational four-year

boarding high school for college preparation. Students

and faculty, cooperating in a work program operate

the school and farm. Under direction of Iowa Friends.

Straight ahead was the east-west roar of cars and trucks on the recently built four-lane Interstate 80. To our left was a small cemetery where Richard Nixon’s great-great-grandmother was buried – a fact that had caused the road planners to curve the interstate slightly so as not to run straight through the cemetery and the school. Instead, it flanked the southern edge of the campus, providing a stark contrast to the pastoral setting.

We turned right into the driveway, where cars had started to accumulate along the extended teardrop-shaped parking area. To our left, hugging the grassy buffer zone of I-80 sat the 100-year-old Hickory Grove Meeting House, a simple, single-story wood frame building that seemed emblematic of the Quaker practice of silent worship and waiting. It looked like it came from another era, with a porch that extended the full length of the building, and two separate entrances that were intended to keep the men and women on separate sides. The original rows of long hard wooden benches had recently been moved a few miles down the road to the Herbert Hoover history site in West Branch and had been replaced with new padded ones.

My nervous excitement bubbled up, though I kept this mostly contained from my father. “If Sarah were here, I would be more expressive,” I thought… “Well, maybe not squealing out loud, but not quite so restrained.”

I was looking forward to this adventure. My sister Laurie had attended Scattergood for the past three years, and her life looked exciting. This was evidenced by her photos and scrapbooks that I pored through whenever she allowed. The scrapbooks were full of clever notes and drawings passed in study hall, table-seating arrangements, parodies of teachers, and programs for plays they had put on. She had found a boyfriend here, who she was destined to spend her life with. This was my turn. What would happen to me?

Madison had been a great place to grow up. I liked it and felt lucky. We lived near the University arboretum with acres of undeveloped land to explore, and it was fertile ground for my imagination. I read youth biographies from the school library about young Native Americans and tried to mimic their walk in the forest. With each step I practiced placing the ball of my foot down before my heel – imagining what life close to the land had been like. Sometimes, I took respite in the branches of a smooth, white-barked sycamore tree when tensions in the family were high. I would climb towards the top and clasp the trunk tightly, drawing energy and sensual comfort from the solid heartwood, then stare across the nearby lagoon while Shay explored the area leash-free, sometimes barking at rabbits.

Of course, there was no overt aggression or violence in our family. We were Quakers. The Society of Friends. But there were unresolved tensions between my parents – unspoken issues that bubbled up to the surface. These were exacerbated when one of my half-brothers had come home to die at the age of 39, from health issues caused by a car accident during his high school years, when, without seatbelts, his head went through the windshield. Later he’d lost a leg in an explosion while working as a chemist for 3M in St. Paul. Now it was almost one year to the day since I had overheard my father say on the phone, while I listened from the top of the stairs in our large brick house, “I think my son has taken his last breath.”

This was his first child to die.

The sense of being Quaker was in my bones, though I had often experienced it as being “other.” My peers in grade school and junior high liked me, but the scope of their knowledge about Quakers was epitomized in the character portrayed on the cylindrical oatmeal box.

“You mean like the Quaker Oats man with the black hat?” they would ask.

My parents, each in their own way, were separated from their families of origin. This left some voids in my sense of rootedness. My father had been born in 1892 on a farm in Pennsylvania to a family with no particular religious connection. His father ordered him never to return home when he announced his intent to go to college. So, he jumped a freight train, and headed west to harvest crops in the Dakotas, earning money for tuition to Oberlin College. At Oberlin he became awakened to Christian values, and when World War I broke out, he volunteered for the Oberlin Ambulance Corps section of the U.S. Army. This experience of driving ambulances on the Italian front, concurrent to Ernest Hemingway driving for the Red Cross, led him to become a committed pacifist the remainder of his life. His parents died before I was born, and I never met any of his three brothers, though I’d heard at least one of them characterized as “farther right than Attila the Hun.” Apparently, they did not share my father’s politics and world view. I’d met his only sister a time or two – a sweet elderly woman who had worked as a nurse. She’d never married but had taken in my youngest half-brother as an infant when his mother died.

My mother was one of thirteen children raised in a German Catholic family on a farm in Michigan. A deeply moral person, she was the only one of the family to leave the Catholic church. In her mid-thirties she married my father – a man eighteen years older, whose wife had died in childbirth with their fifth child. My parents were married in a Friends Meeting in Detroit, and thus began their life as Quakers together, as “convinced Friends.” Most of my mother’s family lived in Michigan, so they were not close by. We saw them rarely and only once had an extended summer visit when both my parents went overseas for separate social justice causes. My siblings and I had spent several days with each family. I was overwhelmed just memorizing the names of my twenty-four aunts and uncles, and more than sixty first cousins. At each place they’d line up the kids for pictures, and I’d struggle to look shorter and blend in, as I inevitably towered over those my same age, thanks to the genes of my father.

When we went to Catholic mass, an aunt would cover my head with a handkerchief, mysteriously saying it was because I was a girl. Once inside the church, I wrestled with the expectations of kneeling, crossing, and holy water. Here I felt like a Quaker, sitting in the crowded pew, surrounded by the visual grandeur of stained glass and statuary, breathing in the unfamiliar musty smell of incense. I wondered, even struggled with, whether I should participate. “Why is this more holy than regular water? Dare I touch it as I pass by the font? Should I kneel and cross myself like everyone else does?”

At Scattergood, I would not have to explain myself. I would be one of sixty high school students from around the country, living together in a community.

My father parked our sturdy Oldsmobile, warm from three hours of travel, along what was called the Main Building. This was the main communal area that housed the girls’ dorm, office, library, auditorium, kitchen, dining room, and art room. All the central campus buildings were situated around a circular sidewalk called “the Circle.” Besides the Main Building, there was a grey-green stucco house, a small frame cottage, an old gym, and on the far side, a two-story boys’ dorm, a laundry and shop building with a bell tower, and a one-story classroom. That’s as much as I could see. Beyond that I knew there was the chicken house, the orchard and garden, more faculty housing, the soccer field, and the new farrowing barn dubbed “The Pig Palace.” My sister had told me stories about how her class dug a deep, narrow ditch to provide water to it, and in her scrapbook was a poetic parody she’d written about it called “Ode to a Ditch.” The school dairy farm and cows were a distance beyond that, across a field.

Several other cars had their doors open, while students and parents unloaded and carried luggage into the building and to the boys’ dorm on the far side of the campus. I sensed anticipation, as though it physically excited the air. My own bags had been carefully packed into the wide trunk of the car and my 3-speed Raleigh bike was strapped on top. I was glad that we had come in the Oldsmobile and not the VW bug that my mother had recently acquired.

Students were allotted a point system, which determined the amount of clothing we could have, since three, sometimes four people lived in each small dorm room, making space limited. I had spent weeks figuring out what to bring, and tediously sewed name tags onto every single item, including socks. For the girls, all skirts had to be long enough to touch the floor when we kneeled, and there were to be no sleeveless tops. We needed durable easy-to-wash clothes that would survive repeated washing with a wringer washer operated by students – a couple of dresses, skirts, blouses, jeans for work, sweaters, lots of underwear and socks, coats, boots, and Bermuda shorts only to be worn for playing hockey and sports. Also, towels, sheets, and blankets.

On the advice of my sister, there was one clandestine item hidden in my luggage – a simple electric immersion coil that could be plugged into an outlet and illicitly used to heat a cup of water for tea or coffee when the dorm rooms got too cold. This device was illegal, and rightly considered a fire hazard, but we ignored the regulation.

Acknowledging that we had arrived after the long drive, my father stretched his lanky arms and turned around to look at me in the back seat. Smiling and pointing to the windshield, he said, “See that bug? He’ll never have the guts to do that again!”

Humor was not a staple in our family, but my father had some one-liners that he liked to repeat again and again. I laughed a bit nervously. At that age I was always somewhat embarrassed of him. Today I was just relieved that he wasn’t wearing his red beret, which drew attention I was trying to avoid. People always thought I was his granddaughter.

He opened the car door, unfolded his long limbs, and climbed out. I followed, intent on scanning any young person I could see to get some clues about what my future would hold. Dad opened the trunk of the car and began to take out suitcases and the footlocker that had been given to me just for this occasion.

I stopped my speculation as we each carried a load, following the sidewalk to the front entrance of the Main Building. Rollers on suitcases had not yet been invented, so we felt the full weight of my possessions. Several people of varying ages sat along a stone wall that flanked the front of the building and chatted familiarly. They smiled as we passed. The clan of Quakers across the country was small, and many knew each other – especially the Iowa families whose children made up a large portion of the students. They had names like Haworth, Hinshaw, Hampton, Chamness, Ellyson, Mott, Rockwell, Henderson, Standing, Moffit… I knew the kids who were coming from Madison, but I did not recognize those that we were passing.

“Laurie probably knows them,” I thought, then asked Dad out loud, “When will Laurie get here?”

“In time for supper, I believe,” he answered, a little breathless from the load he was carrying.

I looked forward to seeing her. She was coming back for her senior year as someone much more worldly than me. Her boyfriend, Larry, had graduated the previous year. Since leaving for Scattergood three years ago, she had spent less and less time at home in Madison, even in the summers. This came as something of a shock to my mother, and I, too, felt somewhat left behind. Now I would have this whole year to get to know her in a new context, and I hoped it would be fun.

Dad and I reached the double glass doors at the front of the Main Building. He held the door open as we took the one step up into the entranceway. We entered the lobby that had a smooth tile floor and a caged reception area to our right surrounded by a formica-topped counter. I knew from prior visits that behind this was the office, with a small living quarters for Leanore, the school director. She was unmarried, so the apartment was minimal. Her office had large picture windows that faced the Circle and the boys’ dorm. From this vantage point, no part of the central campus could escape her gaze – a fact that all students became acutely aware of.

Right in front of us in the center of the lobby was a support post with a hand-written paper sign taped on it that read:

Girls’ Dorm open to men until 5pm

4:30pm Dinner Prep

5:30pm Dinner

Volunteer dishwashers needed

A stairway to the left led down to the lower level, to the kitchen and dining area, and I smelled the sweet, yeasty aroma of fresh-baked bread steaming upwards. Students here made the bread from leftover cereal, and it tasted more delicious than anything available in a store.

We moved through the lobby towards the swinging doors that would take us upstairs to the girls’ dorm, just as a tall, upright woman emerged from the office. She had a broad forehead, neatly cropped hair, no makeup, and wore a simple, one-color suit with a mid-calf skirt, nylons, and sturdy shoes. She moved purposefully towards us, stretching out her hand before seeming to realize that our hands were already full. Her dark brown eyes made direct contact with ours.

“Hello, Chester,” she said, with a wide smile. “And welcome, Jean!”

This was Leanore, and she knew my dad. She had been the director of Scattergood for 18 years and first came as a staff member during World War II when the school closed to become a hostel for European refugees from Nazism – helping them recover and establish new lives. Leanore had a reputation of being tough and was known to be intimidating. She was also practical and resourceful. During her tenure at Scattergood several new buildings had been funded and built. She had steered the school through many challenges, all within a budget based on a per student annual fee of $600 for tuition, room, and board. My sophomore year it jumped to $800. We joked with our parents that it was cheaper for us to go away than to stay at home. Money was always tight. Dad had been on social security for years, which limited the amount of salary he could earn, and Mom had gone back to school in her fifties for a Masters’ degree in Social Work to help support the family.

There was no question that Leanore was a staunch defender of Quaker values and education. She had refused funds from a wealthy Philadelphia donor who wanted her to establish an annual “best citizenship award” for the students. She wanted no part of endorsing an atmosphere of competition. This was a community where all students, staff, and teachers called each other by their first names; education was to be equal for men and women. The curriculum was for college preparation, but no grades were ever given. That meant that students were accepted into college based solely on the track record of previous graduates and on Leanore’s fierce recommendation. You wanted to be on her good side.

Even within this egalitarian structure, when so much responsibility was given to one person, there was room for hypocrisy. Leanore could have a twinkle in her eye, like she did now, but she often behaved like an autocrat. Her presence struck terror in the heart of many students, and I’d overheard some parents say they felt manipulated by her. To be fair, in hindsight, she had to bridge the gap between longstanding conservative traditions and the seething hormonal energy of sixty adolescents, all in coordination with twenty adult faculty. She had to hold the line and it could not have been easy.

As my father now began to chat with her, I felt some intimidation too. In her presence you could feel that she was the seat of authority, not unlike my mother, who was also a frugal and no-nonsense woman. They even looked a bit similar with their short, cropped hair. My mother both embodied and questioned authority. As a young girl, she had visited a convent, thinking she might become a nun. A Sister told her, “If the Priest instructs you to plant a living plant with the flower plunged into the earth and the roots up in the air, you will have to obey.” That had ended it for my mother.

She and I had often butted heads. Sometimes it was about small things. She always wanted things done right. “This is ridiculous, Mom!” I responded when she insisted that I make my unmade bed, even though it was nighttime, and I was just about to crawl into it. When I was young, my family teased that my red hair caused me to have a temper. When I got older, my mother explained that the reason we had conflict was because we were so much alike. The thought horrified me.

Once or twice, after disputing her, she slapped me across the face. It was a shocking moment for both of us, that seemed to come out of another deeper reality, one unconnected to the words I heard around me – perhaps from her own childhood which she rarely spoke about and had separated from. I could never remember what I had said, or what the issues of conflict were. Now, in adolescence, I was beginning to understand how my mother carried the burden of my father’s avoidance of anger and had become the scapegoat of his tendency to deflect responsibility and blame. The more passive he became, the more the buck stopped with her, and she was cast in the role of the “mean one.” In contrast, the memory of his deceased first wife was easy for him and others to idealize, and her angelic presence seemed always able to penetrate the solid brick walls of our house.

Leanore and my father made an interesting juxtaposition as they talked in the lobby. I listened for a while but felt impatient. Now was not the time for rumination. The doors to the dorm swung back and forth as people went in and out – each thumping swoosh reinforcing my urge to run through them and up the stairs.

“I can’t wait a moment longer for Dad, or Laurie or Sarah!” I thought and abruptly excused myself, then turned, and headed up to discover my new life.

Dad put my luggage inside the dormitory doors and went back to the car to get my footlocker and unlash the bike. I bumped my luggage up the two flights of stairs to the long hallway that was to be my new home base. On each side stretched a row of doors, and straight ahead at the end of the hall was the fire escape. The dorm walls were constructed of cement blocks painted an ambiguous pastel color and had a unique musty odor. It’s a smell I recognize to this day, though I can’t describe it. The walls stopped short of the ceiling leaving a gap that ran the length of the hallway between the roof and the walls. We never knew whether the drop ceiling was omitted to save money or to make it easy for the dorm sponsors to see when our lights were on after hours. We students suspected the latter.

I walked down the hall, focusing on the doors that I passed. Each had a handmade cut-out of a dancing star figure with “Hi” in the center and three names written on the points. Halfway down on the left, was a star that read: “Bonnie, Rosy, Jean.” I could hear voices inside, so I paused, leaned in closer and put my hand on the doorknob. These must be my new roommates. Just then I also heard the deep repeated ringing of the large bell in the bell tower being pulled by hand with a rope moving up and down.

“It must be time for the Dinner Prep crew to begin,” I surmised.

In a few minutes, I would go downstairs to get the rest of my things, say goodbye to Dad, and thank him for driving me. He planned to travel on to his oldest daughter Martha’s farm for dinner with her family and would return home to Madison in the morning.

But now I took a deep breath, tightened my fingers, and turned the doorknob.

Jean Graham

The Forms That Hold Us

Currently living in Austin, Texas, Jean Graham is a native Midwesterner with roots in the deep Iowa soil. She attended farm-based Scattergood School in rural West Branch, which sparked her love for making forms out of clay and inspired her life-long interest in ways that art can integrate with, impact, and create community. She has made art happen throughout the country as an exhibiting artist, teacher, museum curator, and public art project manager. Her artworks are included in museum collections and in her own neighborhood. She has an undergraduate degree from New College of Florida and an MFA from the University of Michigan. These days she has time to be an avid gardener, adjusting to the perplexing demands of a changing climate.

Jean is currently writing a memoir, The Forms That Hold Us, that traces her trajectory through the arts and her diverse experiences of culture and the land – from the Midwest to the subtropics and West Africa. She has written essays for exhibition catalogues, contributed a chapter to an anthology on public art, and will be featured as an artist in an upcoming book, ATX Urban Art: Layers of Graffiti, Street Art, Murals, and Mosaics in Austin, TX by J Muzacz.